By Dipak Kurmi

For the first time since the violent 2020 Galwan Valley standoff ruptured decades of hard-earned equilibrium along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), India’s External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, has visited Beijing, symbolically reopening high-level channels of diplomacy. His meetings with President Xi Jinping, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, and Vice President Han Zheng signal a fragile but deliberate recalibration of ties between Asia’s two most powerful neighbours. The visit comes at a moment where mutual strategic distrust is high, the border situation remains tenuous, and yet a confluence of geopolitical imperatives compels both nations to seek common ground.

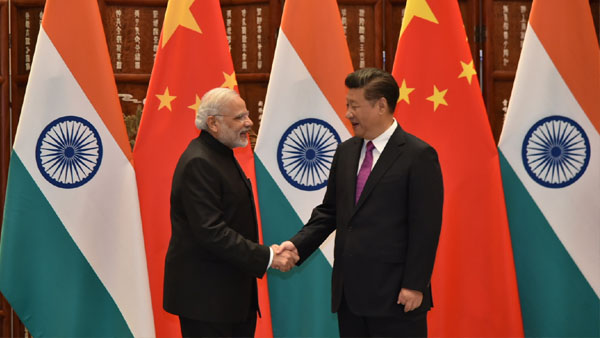

This thaw did not begin in a vacuum. It follows a series of careful diplomatic re-engagements beginning with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s meeting with Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the BRICS summit in Kazan in October 2024. That symbolic interaction set the stage for renewed institutional dialogue. Since then, National Security Advisor Ajit Doval’s December 2024 trip and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s June 2025 visit have laid the groundwork for Jaishankar’s engagement in Beijing ahead of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s Council of Foreign Ministers (SCO-CFM) meet.

These moves signal an unmistakable pattern: India and China are slowly renegotiating a new bilateral order after the old framework, anchored in the 1993 Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement (BPTA), was fundamentally breached in 2020. That treaty had functioned as a stabilising mechanism for nearly three decades. It allowed both countries to compartmentalise their border disputes while expanding trade and cooperation in other areas. But the deadly Galwan clashes shattered that delicate balance, erasing the trust necessary for the “BPTA order” to endure.

What has followed is a more unpredictable era—marked by simmering military friction and economic decoupling strategies. The weaponisation of trade, intensified surveillance along the Himalayan frontier, and hardened rhetoric on both sides have characterised this uneasy interregnum. Unlike the earlier framework where engagement thrived on a foundation of strategic restraint, the current reset operates in a far more transactional and contested space. Even as both sides cautiously resume dialogue, the new foundation is significantly more brittle.

Jaishankar’s trip is emblematic of India’s evolving strategy—what scholars term “competitive engagement.” It accepts the reality that full-spectrum cooperation with China is neither desirable nor feasible under current conditions. Yet, it acknowledges that complete disengagement is both impractical and counterproductive. In this construct, New Delhi is trying to strike a balance: resisting Chinese incursions and influence where necessary, while exploring scope for cooperation where possible. Jaishankar’s articulation that “differences should not become disputes, nor should competition ever become conflict” captures the essence of this approach.

India is not under any illusions. As a country faced with a militarily superior neighbour, it has doubled down on internal capacity building—from defence modernisation and border infrastructure upgrades to expanding diplomatic alliances like the Quad and stronger economic links with Southeast Asia and Europe. Yet, none of these measures offer an instant remedy. External balancing also has limits. The LAC issue remains fundamentally bilateral, and few powers are willing to intervene or mediate due to their own economic dependencies on China.

Consequently, India has chosen a multi-pronged path: continue disengagement in sensitive areas like Eastern Ladakh, maintain military vigilance, and simultaneously foster diplomatic channels to prevent escalation. The current efforts are geared toward crafting a tentative modus vivendi—an informal arrangement that allows coexistence without resolving core disputes. The Indo-China dialogue today resembles more of a containment conversation than one of true rapprochement.

On the ground, disengagement in sectors of Eastern Ladakh has helped prevent fresh clashes, but no durable solution is in sight. The border remains India’s most complex strategic dilemma. It is not merely a cartographic challenge; it is a reflection of how India contends with a revisionist China. The current pause in hostilities should not be mistaken for resolution. Both militaries remain deployed in high numbers, backed by infrastructure that can rapidly escalate tensions.

Meanwhile, economic engagement—a long-time buffer in India-China ties—is under severe strain. The most immediate concern for India is the impact of Chinese export curbs on rare earth magnets, crucial to the electric vehicle (EV) and automotive sectors. These restrictions are already disrupting supply chains and affecting domestic manufacturing. India has rightly responded with production-linked incentives and efforts to develop indigenous alternatives, but building resilient supply chains in rare earths will take years. Jaishankar’s explicit mention of “restrictive trade measures and roadblocks” signals that India is treating economic coercion as a core concern, not a peripheral one.

This economic tug-of-war has broader implications. India wants to avoid dependency while retaining some level of engagement. China’s economic coercion—seen not only in India’s case but globally—has become a signature tool in Beijing’s strategic playbook. New Delhi, like many others, is actively seeking de-risking mechanisms: diversifying suppliers, bolstering domestic capabilities, and participating in international supply chain partnerships, such as those led by the U.S., Japan, and Europe.

Still, some issues remain persistently off-limits—deeply consequential, but diplomatically undiscussed. Chief among them is the Dalai Lama’s succession, a potential geopolitical flashpoint that could erupt in the coming years. China has repeatedly asserted its authority to appoint the next Dalai Lama, while India maintains that it is a spiritual and cultural matter. Despite hosting the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala for decades, India has kept this issue at arm’s length diplomatically, knowing well its inflammatory potential in Beijing.

Equally sensitive is the China-Pakistan axis. Despite India’s well-publicised stance on terrorism and its symbolic rebukes of Islamabad, New Delhi has limited leverage over the Beijing-Islamabad relationship. Strategic, military, and infrastructure investments through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) ensure that Beijing’s interests are deeply entrenched in Pakistan. No amount of diplomatic nudging from India is likely to alter that calculus.

And yet, diplomacy remains India’s best available tool. If the objective is to avert conflict while buying time to build strength, then dialogue, even if circumscribed, is essential. The current track is not about resetting the relationship to pre-2020 status quo—it is about managing a constrained reality. The strategy is less about resolution and more about risk mitigation. In that sense, the idea is to create buffers that reduce the probability of sudden escalation.

What we are witnessing is not détente, but a managed competition. India has limited ambitions in this phase: ensure the border stays calm, reduce economic vulnerabilities, and prevent disputes from spiraling into hostilities. Beyond that, most contentious issues—like territorial claims, Tibet, and strategic alignments—are unlikely to see substantive movement. The best outcome India can hope for is a less uncooperative China.

Looking ahead, the road is steep. More high-level visits will follow. Institutional dialogues may pick up pace. But the structure of the new order remains undefined. The shift from hostility to coexistence is never linear. It will involve setbacks, recalibrations, and calculated ambiguity. India must persist with internal strengthening—militarily, economically, and diplomatically—while leveraging the very uncertainty China introduces into global affairs as an opportunity to deepen ties with like-minded powers.

As the geopolitics of Asia enters a more unstable, multipolar phase, the India-China relationship will be one of the most consequential. It holds the key not just to regional peace, but also to the broader trajectory of global power alignment in the coming decades. In that context, Jaishankar’s visit may be one small step in diplomacy—but it marks an important moment in the long march toward a reimagined equilibrium.

The world’s largest democracy and the world’s most populous autocracy are cautiously exploring a new framework—not of trust, but of tolerance; not of harmony, but of managed tension. The line that divides them may remain contested, but the hope is that it won’t become a fault line of war.

(the writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)