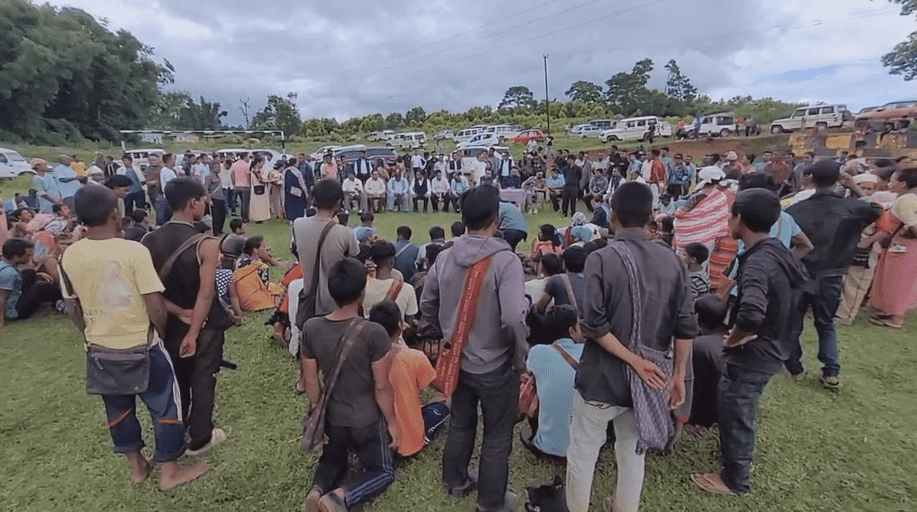

Guwahati, July 8: In one of Assam’s largest eviction operations to date, more than 1,600 families—mostly from minority Muslim communities—were rendered homeless in Bilasipara on Tuesday as bulldozers moved in to clear over 3,500 bighas of khas land. The cleared land is reportedly intended for a thermal power project by the Adani Group.

The eviction was carried out in the revenue villages of Santoshpur, Charuabakhra, and Chirakuta Parts 1 and 2 in Dhubri district. The operation was heavily fortified with police and paramilitary presence. According to the district administration, around 95 per cent of residents had already vacated after receiving official notices, although many still remained until the last moment.

Additional District Commissioner Santana Borah stated that each family was offered ₹50,000 as a one-time rehabilitation grant. However, opposition leaders and local residents claim that only a few families actually received the amount, leaving most without support or alternative housing.

The land is slated for a proposed Adani Group thermal power plant, part of a major investment push in Assam. Located near the Gaurang River and well-connected by rail and road, the site is expected to employ 25,000 workers during construction and create 10,000 permanent jobs once operational. Last month, Adani Group Director Jeet Adani visited two shortlisted sites in Bilasipara and Basbari (Kokrajhar), following a meeting with Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma as part of the ₹50,000 crore investment commitment under Advantage Assam 2.0.

Despite prior warnings, the eviction drive triggered scenes of chaos and distress. Families with young children and elderly members clung to their homes, some dismantling their dwellings themselves while others watched them be torn down. Tensions escalated when Raijor Dal leader and Sivasagar MLA Akhil Gogoi attempted to visit the site but was blocked by police. The standoff led to angry protests, a reported lathi charge, and damage to two JCB machines.

Gogoi later urged the administration to set aside at least 500 bighas from the evicted area for rehabilitating displaced families and demanded that schools, religious structures, and burial grounds be left untouched. He criticized the operation as lacking compassion and legality.

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma defended the drive, calling it part of a broader campaign to evict what he described as “illegal Bangladeshi settlers” occupying government land. Referring to similar operations in Lakhimpur and other districts, Sarma said the evictions were intended to protect the rights of indigenous communities. “If anyone has a problem with the removal of 350 illegal Bangladeshis, they will have to bear it,” he stated. The chief minister added that similar drives would soon be conducted in Chappar and other parts of Dhubri.

The eviction has sparked sharp criticism from opposition leaders and rights groups. AIUDF president and former MP Maulana Badruddin Ajmal denounced the action as “inhuman and discriminatory,” accusing the government of prioritizing corporate interests over citizens’ rights. “These people have lived here for decades. Many have land allotment papers, NRC inclusion, and are on the voter rolls,” he said.

Echoing Ajmal’s concerns, AIUDF MLA Samsul Huda from Bilasipara West said the eviction disproportionately targeted minority communities. “There was a Gauhati High Court order regarding this area, which the government ignored. Even people with legal documentation were evicted,” he claimed. Huda also pointed out that compensation reached only a few families and accused the government of using development as a cover for ethnic targeting.

As Assam clears the way for large-scale industrial projects, the Bilasipara eviction has highlighted the growing tension between development and displacement. For thousands now left without shelter, the promises of economic progress remain distant, while the human cost becomes harder to ignore.