New Delhi, Aug 24 (PTI) African cheetahs brought to India as part of the world’s first intercontinental translocation of big cats will soon roam free again in the wild, nearly a year after they were returned to enclosures in Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park for health check-ups and monitoring, according to officials.

Officials told PTI that the Centre’s Cheetah Project Steering Committee decided on Friday to release the African cheetahs and their cubs, born in India, into the wild in a phased manner after the monsoon withdraws from central parts of the country.

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), the monsoon normally withdraws from most areas in Madhya Pradesh by the first week of October.

“Members of the committee and NTCA (National Tiger Conservation Authority) officials conducted field visits to Kuno and discussed the schedule for releasing the cheetahs. While adult cheetahs will be released into the wild in phases once the rains end, the cubs and their mothers will be released after December,” an official said.

All 25 cheetahs — 13 adults and 12 cubs — are doing well. The animals have been administered vaccines to safeguard them against diseases and given prophylactic medicine to prevent infection, according to the official.

The first batch of eight cheetahs from Namibia was introduced in India in September 2022, and the second batch of 12 cheetahs was flown in from South Africa last February.

The cheetahs were initially released into the wild but were brought back to their enclosures by August last year after the death of three — a female named Tbilisi (from Namibia) and two South African males, Tejas and Sooraj, due to septicemia.

Septicemia is an infection that occurs when bacteria enter the bloodstream and spread.

This condition arose from wounds under the cheetahs’ thick winter coats on their backs and necks, which became infested with maggots and led to blood infections, according to the government’s annual report on Project Cheetah.

Officials had earlier told PTI that the unexpected growth of winter coats by some cheetahs during the Indian summer and monsoon, in anticipation of the African winter (June to September), was a major challenge in managing the animals in India during the first year.

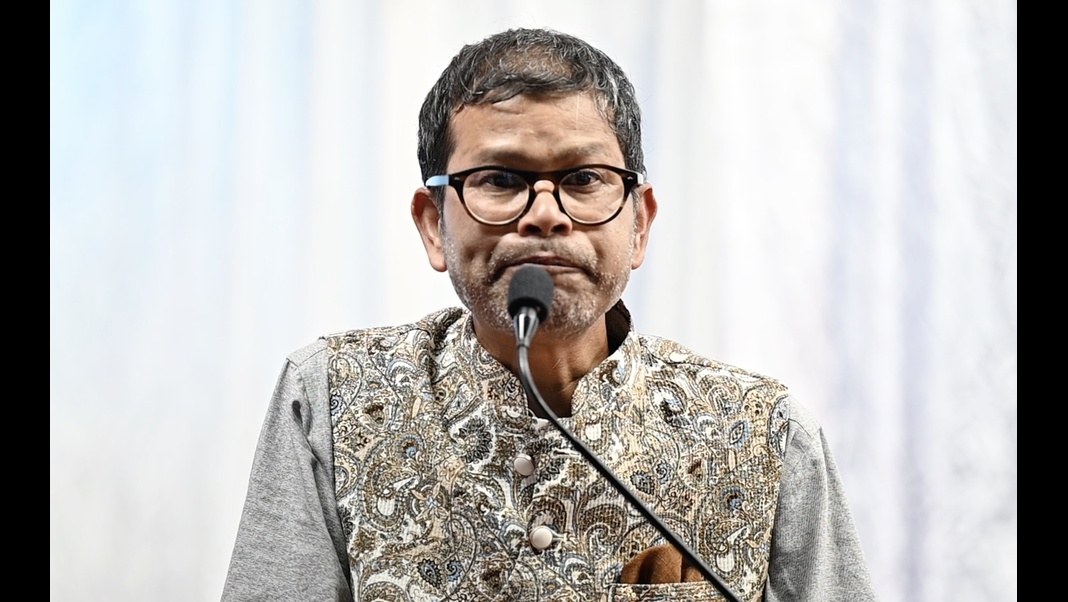

“Even African experts did not expect this. The winter coat, combined with high humidity and heat, caused itching, leading the cheetahs to scratch their necks on tree trunks or the ground. This resulted in bruises and exposed skin, which attracted flies that laid eggs, leading to maggot infestations, bacterial infections and ultimately, the deaths of three cheetahs,” said S P Yadav, Director General of the International Big Cat Alliance and former NTCA member secretary.

The deaths prompted the steering committee to recommend that “future cheetahs for reintroduction should be sourced from countries in the Northern Hemisphere, such as Kenya or Somalia, to avoid biorhythmic complications”.

The steering committee had prepared a plan in December last year to release the cheetahs into the wild, but it was not implemented.

Currently, only one cheetah, named Pavan, is roaming free, with officials noting that he is difficult to spot and capture.

Though such “experimental” projects come with challenges and expected mortalities, experts in both India and Africa have expressed concerns about keeping the cheetahs in enclosures for extended periods.

“The cheetahs are not truly living in the wild, despite spending two years on Indian soil. Cheetahs prefer long journeys, and they could be under severe stress,” an African expert who assisted with the cheetah reintroduction in India said on condition of anonymity.

“Based on global experience and Namibian laws and policies, my understanding is that it is not a good idea to release these cheetahs because of their extremely long period of captivity, especially the captive-born cubs,” said Ravi Chellam, CEO of Metastring Foundation and Coordinator, Biodiversity Collaborative.

Another African expert said the cheetahs are fit enough for the wild if they have been hunting for themselves in enclosures and have not been provided with supplementary feeding.

“They may have also received antiparasitic medications, which could help them during the monsoon, but this might reduce their ability to develop natural immunity to these parasites once they are released,” the expert said.

Since their arrival in India, seven adult cheetahs — three females and four males — have died, including four due to septicemia. All these deaths occurred between March 2023 and January 2024.

Seventeen cubs have been born in India and 12 of them survived. This brings the total number of cheetahs, including cubs, in Kuno to 25, all but one of which are currently in enclosures.