By Dipak Kurmi

The announcement of India’s Goods and Services Tax (GST) restructuring, effective from September 22, 2025, marks yet another chapter in the Modi administration’s approach to economic policy making. Timed strategically with the onset of Navaratri and the festive season, the ostensible simplification of GST from four slabs to two represents what the government portrays as a significant tax reform. However, beneath the veneer of simplification lies a complex web of political calculations, economic necessities, and questions about the true nature of fiscal reform in contemporary India.

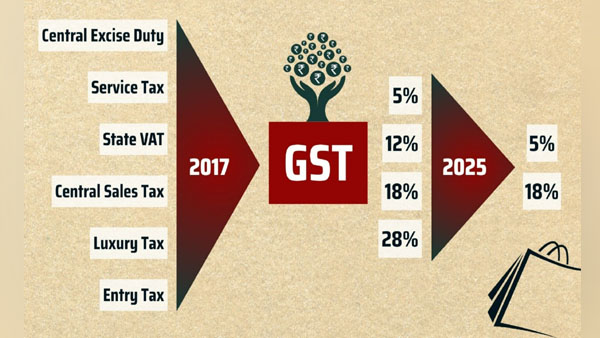

The restructuring reduces the previous four-slab system of 28%, 18%, 12%, and 5% to what is being marketed as a two-slab structure of 18% and 5%. This change comes at a crucial juncture, with the Bharatiya Janata Party facing challenging Assembly elections in Bihar, where Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s weakened position poses additional electoral complications. The timing appears deliberate, designed to create a perception of economic largesse during the festival season when consumer sentiment traditionally peaks.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s candid admission that Prime Minister Narendra Modi instructed her to “please do something with GST” reveals the decision-making process behind this restructuring. This acknowledgment inadvertently exposes the centralized nature of policy formulation in the current administration, where the GST Council, originally conceived as a federal body comprising Union and state finance ministers, appears to function more as an instrument for executing prime ministerial directives rather than as a platform for genuine federal consultation.

The political motivations behind this restructuring become evident when examined against the backdrop of India’s economic challenges and electoral calendar. With the global economy grappling with trade uncertainties and the Indian economy showing signs of sluggishness, the government needed a visible policy intervention that could be marketed as a major reform. The GST restructuring fits this requirement perfectly, offering the appearance of substantive change while essentially representing a reshuffling of existing tax rates.

What the government presents as a two-slab system conveniently omits the 40% slab designated for “sin goods.” This selective presentation raises questions about transparency in policy communication. The 40% slab, which includes items like aerated drinks, caffeinated beverages, and luxury cars, generates substantial revenue despite affecting a smaller consumer base. The moral undertones of labeling these as “sin goods” reflect a paternalistic approach to taxation that goes beyond revenue generation to express societal disapproval of certain consumption patterns.

The redistribution of items across slabs reveals the mechanical nature of this reform. Many goods and services previously taxed at 12% have moved to the 5% bracket, while numerous items from the 18% slab have also been relocated to 5%. Similarly, several products from the erstwhile 28% category now fall under the 18% bracket. This reshuffling, while potentially beneficial to consumers in specific categories, represents more of a rate adjustment than a fundamental reform of the tax structure.

The government’s claim that this restructuring will stimulate economic growth requires careful scrutiny. While lower tax rates on certain goods may boost consumption in those categories, the overall impact on economic growth depends on multiple factors including implementation efficiency, compliance costs, and the broader economic environment. The Modi administration’s self congratulatory stance on India being a leading growth center among major economies, while maintaining sub-seven percent GDP growth, highlights the gap between aspiration and achievement in economic performance.

The lack of transparency in GST data collection and dissemination represents a missed opportunity for evidence-based policy making. When GST was introduced in 2017, then Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian had enthusiastically predicted that the system would provide detailed insights into Indian consumption patterns. However, the government has consistently failed to release slab-wise collection data that could illuminate purchasing power distribution and consumption behaviors across different economic segments. Instead, the public receives only aggregate figures divided between State GST (SGST), Central GST (CGST), and Integrated GST (IGST), along with state-wise collection data.

The total GST collection for 2024-25 reached Rs. 22.08 lakh crores from 1.51 crore taxpayers, with Maharashtra leading state-wise collections. These figures, while impressive in absolute terms, provide limited insight into the distribution of tax burden across different income groups and consumption categories. The absence of detailed slab-wise data prevents meaningful analysis of whether the tax system is achieving its intended objectives of efficiency and equity.

The government’s assurance that televisions, cars, refrigerators, and motorcycles below 1500cc will be cheaper at 18% reflects an understanding of middle-class aspirations but may ring hollow for those struggling with unemployment and economic uncertainty. The irony of expecting gratitude from job-seekers for marginally cheaper consumer durables highlights the disconnect between policy announcements and ground-level economic realities.

This GST restructuring also raises broader questions about the nature of economic reform in contemporary India. The 1991 economic liberalization represented a fundamental shift in India’s economic philosophy, dismantling the license raj and embracing market mechanisms. In contrast, the current GST changes represent incremental adjustments within an existing framework rather than paradigmatic shifts in economic thinking.

The centralization of decision-making authority in the Prime Minister’s Office, as evidenced by Sitharaman’s admission, raises concerns about the erosion of institutional processes designed to ensure federal consultation and consensus-building. The GST Council was conceived as a mechanism to balance central and state interests in tax policy, but its functioning increasingly resembles a rubber stamp for central government decisions.

The marketing of this restructuring as a major reform also reflects the Modi administration’s communication strategy of presenting incremental changes as transformative achievements. This approach may yield short-term political dividends but risks undermining public understanding of what constitutes genuine economic reform and the challenges involved in achieving sustained high growth rates.

Looking ahead, the true test of this GST restructuring will lie not in its immediate political reception but in its long-term economic impact. Will it genuinely simplify tax compliance for businesses? Can it contribute to achieving the double-digit growth rates that India needs to transition to a higher economic trajectory? Will it enhance revenue efficiency while maintaining federal fiscal balance? These questions will determine whether the current changes represent meaningful progress or merely political theater disguised as economic reform.

The GST restructuring of 2025 thus stands as a microcosm of contemporary Indian economic policy making, where electoral considerations, centralized decision-making, and communication strategies often take precedence over rigorous economic analysis and institutional processes. While the immediate beneficiaries may welcome lower tax rates on certain goods, the broader implications for India’s economic governance and reform trajectory merit careful consideration and sustained scrutiny.

(the writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)