DC Pathak

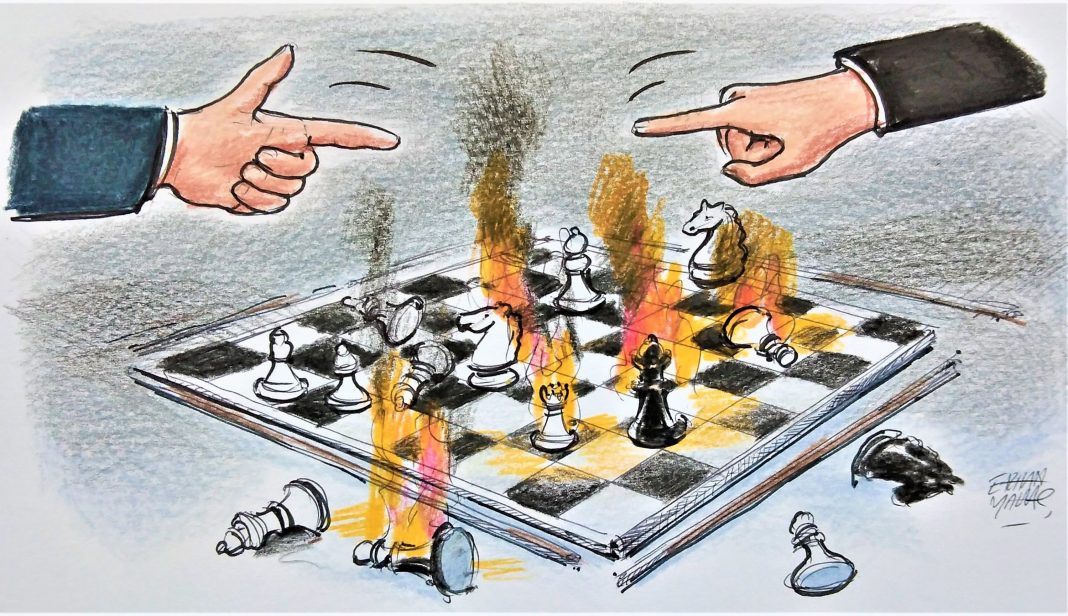

The end of the Cold War in 1991 was known to have opened the floodgate of cross-border conflicts, insurgencies, and separatist violence instigated from outside, all representing a switch over to ‘covert’ attacks in place of ‘open’ warfare.

The pent-up hostilities kept in check by a tense division of the world between two superpowers partly explained why hostile neighbours felt free to settle scores with each other in the belief that they would not attract intervention by large global players. The termination of the Cold War coincided with the rise of terrorism as an instrument of proxy wars.

It is remarkable that Afghanistan, which became the cause of the dismemberment of the USSR, also turned out to be the territory that would provide the run-up to the terror attack of 9/11 on the US, the remaining superpower.

Mullah Omar, Amir of the Kabul Emirate, who assumed power in Afghanistan in 1996, gave a free hand to his close relative, Osama bin Laden, the founder of Al Qaeda. When the US brought down Taliban rule, bin Laden and his Arab cohorts planned the audacious terror attack on the Twin Towers. 9/11 set off the trend of proxy wars—also called ‘asymmetric’ wars—that would use’militants’ rather than’soldiers’ in the covert offensive.

The two biggest international military conflicts of our time have brought out how a ‘war’ was initiated but denied—just because a proxy mode was used for the attack.

The Ukraine-Russia military confrontation started off with the Russian army’s intervention in Ukraine in February 2022. Russian President Vladimir Putin, however, described it as a cross-border ‘operation’ meant to safeguard the interests of the Russian-speaking population of east and south Ukraine that was allegedly exposed to serious discrimination by President Zelensky. Putin avoided using the word ‘war’ for the invasion.

The response of the US-led NATO was to rush military support to Ukraine by way of the despatch of arms and other war material, but without committing any troops on the ground. The lack of membership in NATO for Ukraine came in handy for the US in keeping aid to Ukraine in a proxy mode and not letting a global-level ‘war’ erupt out of the bilateral confrontation. Conflicts sustained by proxy support typically turn into a war of attrition, inflicting huge losses on people—in this case, mostly on the Ukrainian side.

The military offensive of Israel in Gaza was provoked by the surreptitious ‘terror’ attack of Hamas on Israel on October 7 last year, in which some 1200 Israelis were killed and nearly 250, including women and children, were taken away as hostages by the attackers. This was the most recent example of terrorism being used as the instrument of a cross-border military offensive; the Hamas attack was a planned covert attack of a militant body that had progressively turned into an Islamic ‘radical’ outfit.

Hamas viewed the conflict in Palestine as a’religious war’ between Islam and Zionism and not as a mere ‘political’ dispute. This has pushed the Middle East towards a wider regional conflict in which political alignments are being bolstered by religious divides. This is a matter of deep concern for the international community.

The involvement of Iran and its proxies in support of Hamas in the ongoing military pursuit of the Gaza-based outfit by Israel is already producing international repercussions of a kind that would accentuate the trend of a possible return of the Cold War between the US on the one hand and the China-Russia axis on the other.

In the Middle East, Iran and Israel are the two biggest powers with a known history of adversarial relationships. Hamas was originally an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood, the organisation formed by Hasan Al Banna in Egypt and Syria at the height of the Cold War to oppose nationalist pro-Soviet Arab regimes there and call for a return to Islamic rule.

Banna’s thesis was that an Islamic state could exist ‘in competition, not conflict’ with the Western state, and this made the Muslim Brotherhood politically acceptable to the US-led West. However, after the ‘Arab Spring’, the rise of ‘radicalisation’ in the Islamic world changed the character of Hamas as well, and the latter turned into an Islamic radical outfit totally opposed to the US.

Hamas also consequently became far more hostile to Israel, the closest ally of the US, than before. On the other hand, Iran, under the Ayatollahs, represented the rule of Shiite fundamentalism, which is ideologically opposed to capitalism symbolised by the US. Politically, therefore, Iran and Hamas are on the same side of the fence, and this has even overshadowed the religious antagonism that existed between fundamentalist Sunnis and Shiites.

The killing of the political supremo of Hamas, Ismail Haniyeh, in his guest house in Tehran by a precision missile fired from outside the capital city, allegedly by Israel, has precipitated a new crisis between Iran and Israel, with the former threatening revenge for Haniyeh’s death.

Both China and Russia have condemned Haniyeh’s death as a “political assassination” and thus confirmed their alignment with Iran against the US. The US has deployed aircraft carriers in the Gulf to deter Iran from taking any retaliatory action against Israel, underscoring the rise of big-power rivalries in the geopolitically vital Middle East. Iran had already set its proxies—principally Lebanon-based Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthis—upon Israel.

The ascendancy of drones established by the Ukraine-Russia armed conflict—Iran has been the biggest supplier of drones to Russia—is becoming a major reason for the prolongation of cross-border ‘proxy wars’ across the globe. India has directly felt its impact as Pakistan has been using Chinese drones to drop arms and narcotics in the border states of Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab as part of its covert offensive.

In fact, a major concern for India is that the Sino-Pak axis is now far more active—ever since the Indian Parliament abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution in August 2019—in carrying out joint operations aimed at damaging India’s internal security. Pak ISI is behind instigating communal militancy in J&K and elsewhere and pushing it towards faith-based terrorism.

Terrorism by definition is the ‘use of covert violence for a perceived political cause’ and since a ‘cause’ required ‘commitment’ that in turn was measured by’motivation’, the roots of terrorism lay in this motivation that could be ‘ideological’ as in the case of Naxalites, linked to an assertion of ‘ethnic identity’ as in the case of India’s North East insurgencies, or rooted in ‘faith’ as was the case with ‘radical’ Islamic organisations calling for Jehad.

In Islam, the pull of Jehad can be very strong; it was put on par with the five fundamental duties of the faith. Jehad calls for supreme sacrifice for the cause of Islam or in defence of the community of faithful.

Ever since the launch of the ‘war on terror’ by the US-led West following 9/11—first in Afghanistan and then in Iraq—radical Islamic forces have increased their hold in the Muslim world, and this has impacted geopolitics across West & South Asia, Africa and even Europe. Faith-based terrorism has been the instrument of many cross-border offensives, insurgencies and even internal civil wars.

Proxy wars have intensified because of the spread of the narcotics trade, and the new trend of ‘narcoterrorism’, which is now quite visible in both Kashmir and Punjab, is becoming a universal phenomenon. The illicit narcotics trade is creating new vulnerabilities, even for the US’ internal security.

The Pak-Afghan region, after the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, is known more for the patronage extended by Pakistan to the Taliban Emirate at Kabul as well as for the production of high-end narcotics. This has consequently become a great security threat to India, for it has enabled Pakistan to induct Islamic radicals for cross-border terror attacks in Kashmir.

Further, the Sino-Pak strategic alliance that had already enabled China to create the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), cutting through the northern areas of PoK, is now enabling China and Afghanistan to negotiate on opening traffic in the narrow Wakhan strip in north-eastern Afghanistan that separated Tajikistan from Pakistan. This will help to extend CPEC to Tajikistan, linking the landlocked Central Asia to Karachi and Gwadar Port, which would give a tremendous advantage to these two adversaries of India.

At the same time, developments in the Middle East, notably the escalation of the Iran-Israel conflict and the constraints faced by Saudi Arabia, have blocked the progress of the project jointly sponsored by the US and India at the G20 Summit hosted by India in 2023, relating to the economic corridor linking India through Saudi Arabia to Europe, which was a strategic counterbalancing move against China’s Belt and Roads Initiative (BRI).

Iran, it is said, had secured the miniature warhead technology to equip its drones from North Korea through the good offices of China, and all of this created a challenge for India’s policy of maintaining even-handed relationships with Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Iran.

To top it all, the upheaval in Bangladesh caused by a militant agitation against the policies of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, particularly the announcement of the reservation quota, has resulted in her ouster from the country and the takeover by the Army. The agitation had the imprint of support from Pakistan and China.

The anti-Hasina stir, reinforced by the incidents of the killings of a large number of protestors in police firings, became a strong pro-Islamic movement after Sheikh Hasina put a ban on Jamaat-e-Islami, the outfit known for its loyalty to Pakistan. The uprising in Bangladesh, forcing Prime Minister Hasina to flee the country, is being celebrated in Pakistan as a sort of revenge against the bifurcation of Pakistan by India in 1971. Between Pakistan and Bangladesh, the US clearly tilts towards the former.

The Bangladesh Prime Minister had a pro-India disposition, as is well known, and the attack on the Parliament building in Dacca after she left the country indicated that there might be a demand for the return to Islamic rule in Bangladesh. The Hindu minority in Bangladesh was now quite vulnerable in the changed situation there.

There is clearly a threat of organised infiltration of anti-India militants from across the Bangladesh border that is porous in places. India has done well to deploy BSF in additional strength and also keep the army on alert in this regard. Whatever happens in India’s eastern neighbourhood will have a deep impact on India’s strategic interests. The larger picture is that the scene around India, currently marked by proxy offensives, cross-border terrorism, and separatist civil wars, would need careful handling.

(The writer is a former Director of the Intelligence Bureau. Views are personal)