By Dipak Kurmi

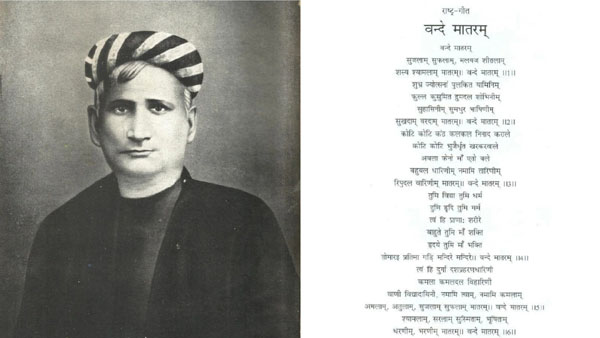

Contemporary debates in India over whether the Constitution embodies secularism or whether slogans like “Vande Mataram” represent patriotism or political provocation cannot be understood in isolation from the subcontinent’s tumultuous history. These seemingly modern controversies trace their roots through centuries of conquest, resistance, accommodation and division, forming a narrative thread that begins not in independent India’s constitutional halls but on medieval battlefields and in colonial drawing rooms. To grasp why such questions continue to provoke passionate responses today requires traversing backward through time to pivotal moments that shaped communal consciousness and political identity in ways that persist across generations.

The year 1194 AD stands as a symbolic watershed in this historical trajectory. When Mohammad Ghori defeated Prithviraj Chauhan in the Second Battle of Tarain, he inaugurated centuries of Muslim political dominance over much of the Indian subcontinent. Some scholars and political leaders have traced the origins of Hindu-Muslim tensions even further back in time. Qaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, architect of Pakistan, once provocatively claimed that Pakistan was born the very day the first Hindu converted to Islam in the subcontinent, suggesting that the creation of a separate Muslim nation was not a twentieth-century political development but the inevitable culmination of an ancient civilizational divide.

Muslims arrived in India through various channels, as conquerors establishing sultanates and empires, as traders and guests welcomed into cosmopolitan ports, or as converts from within the existing population. Few could claim unbroken native descent from the soil itself, a demographic reality that would later fuel debates about belonging and legitimacy. Among the rulers who established Muslim dynasties across India, the spectrum of governance ranged widely. Some proved benevolent administrators who enriched Indian culture and promoted religious tolerance, others governed harshly through military might and taxation, and a destructive minority left legacies of temple demolition and forced conversions that would haunt communal memory for centuries.

The brightest chapter of Muslim rule in India undoubtedly belongs to Emperor Akbar, whose remarkably long and liberal reign during the sixteenth century brought unprecedented harmony to the subcontinent. Akbar’s court became a crucible of cultural synthesis, where Persian aesthetics merged with Indian traditions, where Hindu Rajput warriors served as valued generals and administrators, and where intellectual debate flourished across religious boundaries. His policy of sulh-i-kul, or universal peace, represented an early experiment in pluralistic governance that acknowledged India’s religious diversity as a strength rather than a problem to be solved through conversion or coercion.

In stark contrast stands Aurangzeb, whose austere religiosity and reimposition of the jizya tax on non-Muslims marked the darkest chapter of Mughal rule. His intolerance alienated Hindu subjects and regional rulers, fracturing the delicate accommodations his predecessors had carefully constructed. Aurangzeb’s long reign witnessed almost continuous warfare, from the Deccan to the northwest, as he attempted to expand and consolidate an empire that was already beginning to fray at its edges. The resentments generated during his rule would contribute significantly to the Mughal Empire’s eventual fragmentation.

One of history’s enduring puzzles concerns the absence of sustained, united Hindu resistance to the Sultans and Badshahs of Delhi. Despite repeated invasions and centuries of Muslim political dominance, no pan-Indian uprising materialized to challenge this order. Regional heroes emerged whose courage and statecraft deserve commemoration. Shivaji Bhonsle stands preeminent among these figures, establishing Maratha power through brilliant guerrilla tactics and administrative innovation, yet his influence remained largely confined to the Deccan plateau. Maharana Pratap of Mewar fought heroically against Akbar’s armies, refusing to submit even after the devastating Battle of Haldighati, but his struggle too remained geographically limited. The failure to forge broader coalitions meant that Muslim political supremacy continued relatively unchallenged until external forces intervened.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the declining Mughal order created a power vacuum that various regional forces competed to fill. Among the most consequential developments was the reckless governance of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the young Nawab of Bengal, whose alienation of his own officers, bankers and merchants pushed them into alliance with the East India Company. Their support proved decisive in ensuring Robert Clive’s victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, a confrontation that opened Bengal’s immense wealth to British exploitation and marked the beginning of colonial domination over the subcontinent. Subsequent British military victories over Tipu Sultan in Mysore in 1799 and the annexation of Awadh under Lord Dalhousie’s controversial Doctrine of Lapse completed the systematic dismantling of Muslim political authority across India.

The Revolt of 1857 briefly shook British confidence in their empire’s permanence. For one tumultuous year, large swaths of North India burned with rebellion as sepoys, dispossessed aristocrats and peasants united against colonial rule. The uprising’s suppression proved brutal and definitive. In 1858, Queen Victoria assumed direct control over India, ending the East India Company’s administrative fiction, and two decades later, in 1877, she was proclaimed Empress of India in an elaborate durbar that symbolized Britain’s complete dominance. British authorities concluded that Muslims had been the principal instigators of the revolt and punished them more severely than Hindu participants, confiscating estates, excluding Muslims from government service and viewing the community with lasting suspicion.

This perception deepened Muslim resentment and nostalgia for lost political power. Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, founder of the influential Aligarh Movement that sought to reconcile Muslims with British rule and modern education, even argued that when the British eventually departed India, they should return governance to the Muslims from whom they had conquered it. Whether this represented political foresight or wishful delusion remains debatable, but it revealed the depth of Muslim belief in their natural right to rule the subcontinent.

Ironically, the Indian National Congress, often branded by critics as essentially a Hindu party, was not founded by Hindus at all but by Allan Octavian Hume, a retired English civil servant, in 1885. Hume envisioned the Congress as a safety valve for Indian political aspirations, channeling dissent into constitutional petition rather than rebellion. Yet by 1906, Muslims had established their own separate political platform through the All-India Muslim League, reinforcing the belief among both communities that while Hindus excelled as traders, cultivators and administrators, Muslims were inherently suited for political leadership and military command. This sentiment persisted even after Mahatma Gandhi entered India’s political scene in 1915.

Gandhi’s early political strategy employed curious methods to bridge Hindu-Muslim divisions. To demonstrate solidarity, he supported the Khilafat Movement launched by the Ali brothers, Mohammad and Shaukat, to restore the Ottoman Caliphate after World War I stripped the Turkish sultan of temporal power. Astonishingly, Gandhi even served as President of the Khilafat Committee, formed to defend a distant Turkish ruler thousands of miles removed from Indian concerns. Many contemporary observers interpreted this as confirmation that political power in India still fundamentally revolved around accommodating Muslim leadership and sensibilities. Gandhi’s satyagraha, though morally compelling as nonviolent resistance, appeared to skeptics as primarily a moral appeal rather than a genuine political challenge to imperial authority.

In March 1940, at Lahore, Jinnah formally declared that Hindus and Muslims constituted “two distinct nations” incapable of coexisting within a single state. No prominent Indian voice mounted a sustained public challenge to this claim. When the premiers of Punjab and Bengal initially opposed Partition, Congress leaders quietly welcomed their resistance, believing Jinnah’s separatist vision would ultimately fail for lack of practical support. Yet by May 1947, Lord Mountbatten announced the Partition plan, confirming that Jinnah’s will had prevailed. Once again, Muslim political determination had shaped the subcontinent’s destiny.

Partition’s aftermath proved tragic and demographically lopsided. In Pakistan’s western wing, Hindu and Sikh populations were virtually eliminated through violence and forced migration by 1948. The eastern wing, later Bangladesh, saw its Hindu population plummet from thirty-three percent at Partition to barely eight percent over subsequent decades. Migration patterns revealed stark asymmetry: millions of Hindus fled Pakistan seeking refuge in India, while relatively few Muslims departed India for Pakistan. This imbalance reinforced perceptions that political initiative and assertiveness in the subcontinent remained disproportionately concentrated among Muslims rather than Hindus.

This historical backdrop illuminates why contemporary debates surrounding patriotic expressions like “Vande Mataram” evoke anxieties rooted in centuries of contested power. Some Muslim leaders continue behaving as though their community still sets the fundamental terms of national discourse, an illusion that perpetuates misunderstanding and hinders genuine social harmony.

India’s past proves too complex for reduction into simplistic communal binaries. Both Hindus and Muslims have shaped the nation’s destiny through contributions noble and ignoble, constructive and destructive. Yet national progress demands sober recognition of historical facts rather than romanticized memories of lost empires or imagined privileges. Authentic secularism lies not in selective appeasement but in equal accountability across communities. A nation’s maturity manifests not through the volume of its grievances but through its capacity to confront history without distortion or denial.

Ultimately, “Vande Mataram” should unite rather than divide Indians, reminding all citizens of shared soil and common destiny. History may bear scars of conquest and partition, but the future must rest on reason and reconciliation. Every citizen, regardless of religious identity, must recognize that the power to shape India’s tomorrow lies not in nostalgia for vanished glories but in unity of purpose and respect for truth. Only through such recognition can the Vedantic spirit of oneness and universality truly prevail.

(the writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)