By Satyabrat Borah

In recent years, residents of Assam and the broader Northeast India region have increasingly felt the ground tremble beneath their feet with alarming regularity. People often remark that earthquakes seem to be occurring more frequently, citing events like the moderate tremor of around 5.6 magnitude that shook the region not long ago. This perception raises profound questions: Are earthquakes truly becoming more common in Assam? What do these seismic events signify for a region already classified as one of the most vulnerable on the planet? And perhaps most crucially, what lessons can we draw to safeguard lives and infrastructure in the future? This phenomenon is not merely a matter of fleeting tremors but a reminder of the immense tectonic forces at play beneath the Earth’s surface, forces that have shaped the landscape of Northeast India for millions of years.

Earthquakes are fundamentally the result of sudden releases of energy accumulated within the Earth’s crust. The planet’s outer layer is divided into massive tectonic plates that float on the semi-fluid mantle below. These plates are in constant, albeit slow, motion, driven by convection currents in the mantle. When plates interact along their boundaries, stress builds up over time. Eventually, this stress exceeds the strength of the rocks, causing them to fracture or slip along faults. The released energy propagates as seismic waves, shaking the ground and potentially causing devastation. The intensity of an earthquake is measured on the Richter scale or, more accurately today, the moment magnitude scale, where each whole number increase represents about 31 times more energy release. A magnitude 5 event can cause considerable damage in populated areas, while those above 7 are considered major and capable of widespread destruction.

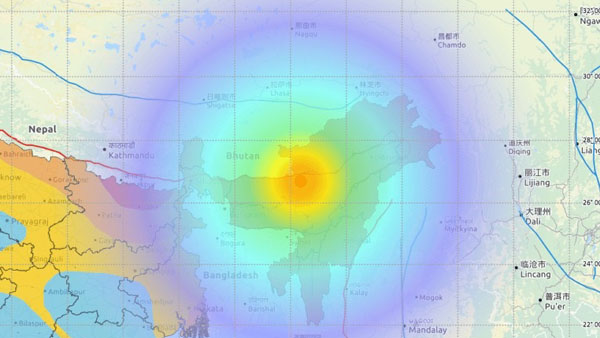

Northeast India, including Assam, sits at the confluence of several tectonic plates, making it one of the most seismically active regions globally. The primary driver is the ongoing collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. The Indian Plate is moving northward at a rate of about 5 centimeters per year, thrusting beneath the Eurasian Plate and uplifting the Himalayas. This subduction and collision create immense compressional forces. In Assam specifically, additional complexity arises from the interaction with the Burma Plate to the east, leading to a network of active faults. Key structures include the Main Himalayan Frontal Thrust, the Kopili Fault, the Dauki Fault, and the Mishmi Thrust. Assam falls entirely within Seismic Zone V, the highest risk category in India’s zoning map, indicating the potential for intensities exceeding IX on the Modified Mercalli scale, where even well-built structures can collapse.

The historical record underscores this vulnerability. Two of the most catastrophic earthquakes in recorded history struck this region. The 1897 Great Assam Earthquake, with an estimated magnitude of 8.1 to 8.3, originated near the Shillong Plateau. It devastated vast areas, killing over 1,500 people, liquefying soils, and altering river courses. Buildings in Shillong were flattened, and the tremors were felt as far as Calcutta. This event provided early insights into fault mechanics, as British geologist Richard Dixon Oldham analyzed global seismograms to identify distinct wave types. Even more devastating was the 1950 Assam-Tibet Earthquake, registering a magnitude of 8.6, one of the largest instrumentally recorded earthquakes ever. Its epicenter lay near the Mishmi Hills on the Assam-Arunachal border. The quake triggered massive landslides that dammed the Brahmaputra River’s tributaries, leading to catastrophic floods when the dams burst weeks later. Over 4,800 lives were lost, entire villages vanished, and the landscape was profoundly altered, with rivers changing paths and forests uprooted. Pilots reported seeing the ground “ripple like waves” from the air. These events highlight the potential for mega-thrust earthquakes in the Himalayan arc, where centuries of strain accumulation can unleash in moments.

In more recent times, seismic activity has continued unabated. The region experiences hundreds of small tremors annually, many too minor to be felt. However, moderate events periodically remind residents of the underlying threat. In 2021, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck near Sonitpur, causing damage in Guwahati and surrounding areas. But the year 2025 saw a notable uptick in perceptible shakes. On September 14, 2025, a magnitude 5.5 to 5.9 earthquake centered in Udalguri district rattled Assam, with shallow depth amplifying the felt intensity. Tremors spread to Guwahati, where people rushed out of buildings in panic, and extended to neighboring states, Bhutan, and even parts of Bangladesh. No major casualties were reported, but it sparked widespread concern. Throughout 2025, smaller events dotted the calendar: a 4.5 in Dhekiajuli in December, clusters in November where Assam recorded nine quakes, the highest for any Indian state that month, and various 3 to 4 magnitude shakes in districts like Darrang, Morigaon, and Sonitpur. By late 2025, monitoring stations detected dozens of events within 100 kilometers of key cities like Guwahati and Tezpur. Entering 2026, activity persisted with occasional moderate tremors felt in the region.

This apparent cluster of events leads many to wonder if earthquake frequency is genuinely increasing. Scientifically, the answer is nuanced. Globally and regionally, the long-term rate of earthquakes has remained relatively constant over centuries. What has changed is detection capability. Modern seismographic networks, including those operated by India’s National Center for Seismology and international bodies like the USGS, now record thousands of small quakes annually that went undetected in the past. In Northeast India, the expansion of monitoring stations has similarly improved sensitivity. Data from the past decade shows an average of 70 to 100 earthquakes of magnitude 4 or above within 300 kilometers of Assam each year, a figure consistent with historical patterns when adjusted for detection. Clusters like those in 2025 are normal in active zones; they often represent aftershocks or stress redistribution along faults. However, some studies suggest that ongoing plate convergence is building strain in “seismic gaps” areas dormant since major events like 1950, potentially foreshadowing a larger release. Probabilistic hazard assessments indicate high peak ground accelerations possible in future great earthquakes.

Yet, perception of increased frequency stems from real factors. Population growth and urbanization in Assam have placed more people in harm’s way. Guwahati, a rapidly expanding metropolis on alluvial soils prone to amplification of seismic waves, is particularly at risk. Many buildings, especially older ones or those in informal settlements, do not adhere to earthquake-resistant codes. Liquefaction, where saturated soils behave like liquids during shaking, remains a hazard in the Brahmaputra Valley. Climate change may indirectly exacerbate risks through altered monsoon patterns leading to more landslides that trigger or accompany quakes.

These frequent tremors serve as critical warnings. They indicate that the region’s faults are active and capable of accommodating slip in small increments or, cumulatively, in catastrophic events. The Kopili Fault, for instance, has been implicated in several recent moderate quakes and is considered capable of producing magnitude 7 events. The “Assam Gap” along the Himalayan front has not ruptured in a great earthquake since 1950, accumulating significant strain. Experts warn that a repeat of 1897 or 1950 could cause tens of thousands of casualties and economic losses in the billions, given today’s denser population and infrastructure.

Preparation is thus imperative. India has made strides with the National Earthquake Monitoring Network, early warning systems in pilot stages, and building codes updated post-2001 Bhuj earthquake. In Assam, the state disaster management authority conducts drills and retrofitting programs. Individuals can contribute by securing furniture, preparing emergency kits, and learning the “Drop, Cover, and Hold On” protocol. Communities should advocate for enforcement of seismic standards in construction, especially in high-rises mushrooming in Guwahati. Schools and workplaces need regular evacuation practices. Research into paleoseismology trenching old faults to uncover past ruptures can refine hazard maps.

The recent earthquakes in Assam do not necessarily signal an imminent apocalypse but underscore a perpetual reality: living in harmony with an active Earth. They signify ongoing tectonic adjustment in one of the world’s most dynamic convergent zones. Rather than viewing them with helpless fear, we should interpret them as calls to action. Enhanced monitoring, public education, resilient infrastructure, and regional cooperation with neighboring countries sharing similar risks can mitigate future impacts. By heeding these ground-shaking alerts, society can transform vulnerability into preparedness, ensuring that when the next major event strikes, the toll is measured in resilience rather than tragedy. The Earth’s plates will continue their inexorable dance, but human foresight can determine how gracefully we endure it.