Dipak Kurmi

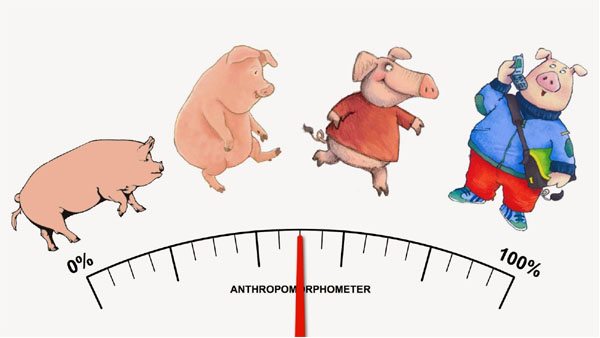

The literary device of humanizing animals, objects, and abstract concepts has been a fascinating technique employed by writers since ancient times, capturing the imagination of audiences across generations. This practice, known as anthropomorphism, infuses non-human elements with human attributes, thereby creating compelling narratives that resonate deeply with readers. From ancient fables to contemporary storytelling, the humanization of non-human entities is a craft that requires skill, creativity, and insight.

The use of anthropomorphism is especially popular in children’s literature, where it fosters engagement and imparts moral lessons in an accessible manner. Talking animals like dogs, cats, and even wolves have delighted young readers for centuries. One of the most notable examples is the portrayal of the wolf in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a tale that has seen countless adaptations and retellings. The wolf, endowed with cunning and speech, adds depth and menace to the narrative, illustrating how anthropomorphism can enrich a story’s thematic elements.

One of the most enduring and inspiring works that exemplifies anthropomorphism is The Adventures of Pinocchio, written by Italian author Carlo Collodi in 1883. Collodi’s choice to craft Pinocchio as a wooden puppet imbued with human desires, flaws, and aspirations set the story apart from conventional tales of human protagonists. Pinocchio’s longing to become a real boy, combined with his propensity for lying and the consequences thereof, strikes a chord that would have been less engaging had the protagonist been an ordinary boy. The story’s universal themes of honesty, growth, and redemption have allowed it to transcend time and culture, inspiring various adaptations, including Disney’s 2022 film Pinocchio and Pinocchio: A True Story by Lionsgate, as well as adaptations in other formats such as Korean dramas.

While certain tales, such as Pinocchio, adapt seamlessly into both literature and film, there are narratives that thrive exclusively in one medium. For instance, the animated film Cars (2006), produced by Pixar, showcases anthropomorphic vehicles. The film’s vibrant world, populated by sentient cars that race, converse, and experience personal growth, captivated audiences and was a commercial success. However, such a concept might not translate effectively to the written word due to the lack of visual and auditory elements that are crucial for engaging the audience in this context.

The humanization of non-human characters is not confined to children’s literature. It has also been a powerful tool in adult fiction, as exemplified by George Orwell’s novella Animal Farm. In this allegorical masterpiece, Orwell imbues pigs and other farm animals with human characteristics to craft a potent critique of totalitarian regimes. The closing line, “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which,” leaves an indelible impression, illustrating the erasure of distinctions between the oppressors and the oppressed.

Authors have even extended anthropomorphism beyond tangible objects and animals to abstract concepts. Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Emperor of All Maladies is a landmark example of how non-fiction can incorporate this literary device. Mukherjee, an oncologist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, personifies cancer, casting it as an adversary in a war replete with victories, defeats, heroes, and martyrs. His portrayal of the disease transforms a medical history into a gripping narrative akin to a detective story, drawing readers into the relentless and deeply human struggle against a formidable foe. Mukherjee’s personal connection—his father succumbed to cancer—imbues the work with poignancy and authenticity, amplifying its impact.

The potential for such literary devices extends to other modern adversaries as well. For example, while there have been numerous works of fiction centered around the COVID-19 pandemic, no significant work has emerged where the virus itself is anthropomorphized. This gap presents an intriguing opportunity for creative exploration. The crafting of a character to represent a virus such as SARS-CoV-2 would demand thoughtful consideration of its traits: its stealth, its global spread, and its multifaceted impact on human lives. Notably, choosing to personify the virus as female might align with its invisible, pervasive nature—“Madame Corona” could embody the insidiousness and unpredictability of the disease.

Achieving a convincing anthropomorphism of something intangible, like a virus or a disease, is a formidable task. It requires aligning the entity’s attributes with characteristics that readers can recognize and engage with. Unlike illnesses such as smallpox or polio, which left visible marks on sufferers, COVID-19’s impact is less immediately perceptible. This subtlety could be leveraged to shape a character that is both alluring and lethal, capable of embodying traits that evoke a complex response from readers.

The challenge extends beyond disease. Air pollution, identified by the World Health Organization as a leading cause of death with an estimated seven million casualties annually, presents another opportunity for literary humanization. The deaths from outdoor and indoor air pollution, numbering 4.2 million and 3.8 million respectively, call for awareness and action. A character personifying air pollution—a spectral, omnipresent figure slowly asphyxiating urban populations—could resonate profoundly with readers living in densely populated, polluted cities. Such a narrative could evoke a sense of urgency, compelling audiences to confront the consequences of their environment in a visceral way.

Anthropomorphism goes beyond storytelling; it engages the reader’s empathy and imagination. Through it, authors can bring attention to real-world issues, whether it be the unchecked spread of disease, the silent threat of pollution, or political and societal decay. While the humanization of animals and objects is a well-trodden path in literature, the personification of abstract or contemporary threats requires an author with the skill to balance fact and fiction. Writers capable of weaving these elements seamlessly can transform otherwise mundane or invisible perils into stories that resonate with a wider readership and inspire reflection, advocacy, and change.

As modern challenges evolve, so must literature. Writers are called to broaden their scope and experiment with anthropomorphism in new contexts. Whether it is an ambitious tale where pollution becomes a villainous character or a virus morphs into a spectral antagonist, the potential for poignant, thought-provoking stories is immense. For authors ready to tackle such ambitious projects, the canvas of anthropomorphism offers infinite possibilities.

(the writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)