By Dipak Kurmi

India closed 2025 with a sense of economic confidence that has been rare in its post-Independence history. Growth has stabilised at a higher trajectory, edging steadily towards the elusive but increasingly plausible target of sustained eight per cent-plus annual expansion. This momentum stands in sharp contrast to the first four decades after 1951, when India’s average annual real growth rate languished at a modest 4.2 per cent. During that long period, growth crossed seven per cent in only five isolated years and touched nine per cent just twice, never managing to sustain such performance in subsequent years. Structural rigidities, a closed economy, and limited industrial competitiveness ensured that high growth remained episodic rather than enduring. The liberalisation era that began in 1992 marked a clear break, consolidating growth outcomes over the next quarter-century. Between 1992 and 2014, India achieved an average annual growth rate of 6.1 per cent, with only three years dipping below four per cent and another three years exceeding eight per cent. While this represented progress, it still fell short of transforming India into a consistently high-growth economy. The decade following 2014, however, tells a more encouraging story. Excluding the two years of disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic between 2019 and 2021, India recorded average annual growth of 7.4 per cent in the five years preceding the pandemic and 7.2 per cent in the four years that followed. With growth of 6.5 per cent in 2024, the highest in the Indo-Pacific region after Vietnam’s 7.1 per cent, and an anticipated 7.5 per cent in 2024–25 with upside potential thereafter, India today possesses the macroeconomic momentum required for sustained eight per cent-plus growth, even if it remains a stretch target rather than a guaranteed outcome.

This growth story is reinforced by relatively strong fiscal fundamentals. India’s fiscal metrics, while not pristine, compare favourably with many major emerging economies. The Centre’s fiscal deficit, which ballooned to 9.2 per cent of GDP during the Covid pandemic, is now on a visible consolidation path towards the long-stated norm of four per cent. Total public debt stood at about 81 per cent of GDP in 2024 according to IMF estimates, lower than Brazil’s 95 per cent and dramatically below China’s 205 per cent, though higher than South Africa’s 66 per cent. India’s inclusion in the JP Morgan Global Bond Market Index for emerging economies in 2024 marked a significant milestone, beginning with a one per cent weight that rose to 10 per cent in 2025. This has enhanced India’s global financial visibility and subjected its investment risk metrics to greater international scrutiny, an outcome that can encourage fiscal discipline over time. Domestic capital markets have mirrored this confidence. Despite sharp volatility during 2025, equity markets ended the year roughly 15 per cent higher than the previous year, buoyed by strong domestic inflows seeking returns. These flows have been supported by relatively liberal credit conditions and the prospect of further interest rate reductions should low inflation persist, particularly inflation anchored by benign food prices. Together, fiscal consolidation, capital market vibrancy and improving global financial integration provide a stable macroeconomic backdrop for India’s growth ambitions.

Yet beneath this optimistic surface lie persistent structural clouds that threaten to cap India’s long-term potential if left unaddressed. The first is India’s weak industrial competitiveness, a vulnerability starkly exposed by its decision to voluntarily exit the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. RCEP, which accounts for nearly one-third of global GDP, was perceived as a threat to domestic industry due to the risk of cheap manufactured imports originating in China, often routed through Chinese-owned entities in Southeast Asia. India’s concern was not unfounded, but the exit also underscored the cost of decades of protection that dulled innovation, efficiency and entrepreneurial risk-taking. The alternative trade grouping, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, from which the United States withdrew in 2017 and which excludes China, covers only 18 per cent of global GDP and offers limited compensatory advantages. The core issue remains domestic competitiveness. Historically, inadequate infrastructure and high logistics costs, often in double digits as a share of GDP, eroded the cost efficiency of Indian manufacturing. Encouragingly, logistics costs have now fallen to a globally competitive 7.9 per cent of GDP, reflecting sustained public investment in transport infrastructure. Combined with a policy thrust towards artificial intelligence, deeper digitalisation and experiments with Central Bank Digital Currencies under the Reserve Bank of India’s supervision, there is renewed hope that Indian industry can close the competitiveness gap. Lower logistics costs are especially significant for medium and small enterprises, which account for 40 per cent of exports, one-third of industrial output and about 30 per cent of GDP. As these firms gain from efficiency improvements, resistance to rationalising import safeguards may gradually weaken, enabling deeper integration with global value chains.

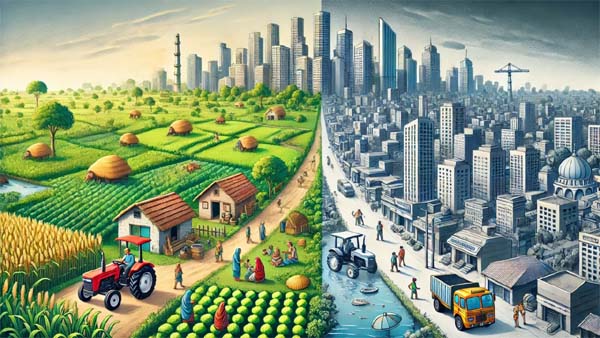

The second and arguably more intractable cloud is India’s uncompetitive agricultural sector. Agriculture continues to absorb roughly one-third of the workforce, much of it in the form of excess or disguised unemployment, even as its contribution to GDP has steadily declined. Politically, meaningful agricultural reform has proven elusive. The Bharatiya Janata Party, like the Congress before it, lacks deep historical roots in rural political mobilisation, making it wary of confronting entrenched farm interests. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has attempted to offset this constraint through expansive welfare measures, channelling benefits to around 100 million rural families, including annual cash transfers of Rs 6,000 per family. State governments have layered additional transfers on top, with some southern states providing up to Rs 13,000 per family per year. While these transfers offer short-term income support, they have not altered the underlying structure of agriculture. Farming remains insufficiently liberalised and commercialised, with individual cultivators locked into cereal-centric cropping cycles dominated by wheat and rice. This pattern persists largely due to a long-standing regime of administered cost-plus pricing and state procurement, which absorbs more than one-third of marketable cereal output. While this system provides price support, it also distorts incentives, discourages diversification and innovation, and exposes farmers to policy risk through export bans imposed whenever domestic retail prices rise. Subsidised inputs such as fertiliser, electricity and irrigation water impose heavy fiscal burdens on state governments, while perpetuating inefficient practices. The contrast between stagnant farm productivity and market-driven factory production has grown starker over time, reinforcing the drag that agriculture imposes on overall growth.

The third cloud is deeply political and cuts across India’s institutional architecture. Nearly two-thirds of Indians live in rural areas, making agriculture and rural livelihoods central to electoral outcomes. Any political leader who successfully liberalises agriculture while balancing the competing interests of farmers, traders and farm labour could capture the enduring loyalty of the electorate and reshape India’s political landscape. Yet party structures remain reluctant to vest such transformative authority in a single individual. Both major national parties are urban-centric, short of leaders willing or able to engage patiently with the complexities of rural political economy. Compounding this is the inherently centralised nature of India’s Union government, shaped by colonial instincts and design. From Rajpath in the past to Kartavya Path today, New Delhi has remained sceptical of bottom-up solutions and deep reform of grassroots institutions. The persistent neglect of democratic, administrative and fiscal empowerment at the panchayat level, where most Indians live, and in cities that house the rest, reflects a statist mindset that privileges central control over community decision-making. This approach is reinforced by an intellectual fascination with global reform templates, popularised by elite forums such as the World Economic Forum, which emphasise rapid gains from global trade in services and manufacturing. These models leave little space for the slow, granular work of rural transformation that India urgently requires.

The cost of this neglect is becoming increasingly visible. Stagnant rural incomes suppress demand for consumption goods, narrowing the personal income tax base and constraining government revenues. To compensate, the state relies heavily on indirect taxes, which distort consumption patterns and weigh disproportionately on the poor. High welfare payouts strain public finances, while elevated public investment in industrial infrastructure becomes necessary to offset weak private demand. Most troubling of all is the growing alienation of the bottom half of India from the benefits of economic prosperity. Latent rural human potential remains underutilised, feeding back into the economy as a structural constraint on sustainable growth. India’s recent performance demonstrates that macroeconomic stability, fiscal prudence and industrial efficiency can propel growth towards historic highs. But without unlocking rural potential through genuine agricultural reform and grassroots empowerment, this momentum risks plateauing. Sustained eight per cent-plus growth will ultimately depend not only on capital markets, trade policy or digital innovation, but on reconciling India’s growth story with the lived realities of its rural majority.

(the writer can be reached at dipakkurmiglpltd@gmail.com)