ROOPAK GOSWAMI

Guwahati, Jan 21: The North East’s natural richness comes not only from its forests, birds and animals that we know and can see, but also the flourishing habitats of microorganisms that make the region a biodiversity hotspot.

In yet another milestone, Meghalaya has been found to be a key contributor to the region’s biodiversity as a rare microorganism has been discovered in the state, first time in India.

Documentation of the microorganism – never recorded in India – in Meghalaya’s freshwater habitats along with Arunachal Pradesh’s forest ecosystems highlighted the North East’s biodiversity far beyond its well-known wildlife.

Scientists from the Zoological Survey of India have recorded the testate amoeba genus Sphenoderia in India for the first time, with the species recorded from freshwater sediments in Meghalaya and moss-covered forest habitats in Arunachal Pradesh.

It was found from Nan Shnong lake in Meghalaya and Talle Valley Wildlife Sanctuary in Arunachal Pradesh. Nan Shnong Lake (often referred to locally as Nan Shnong Nongthymmai / Lum Thangding) is a small lake located near Laitlyngkot village in East Khasi Hills district. It is around 30 km from Shillong city, 1 hour drive from Shillong-to-Dawki road.

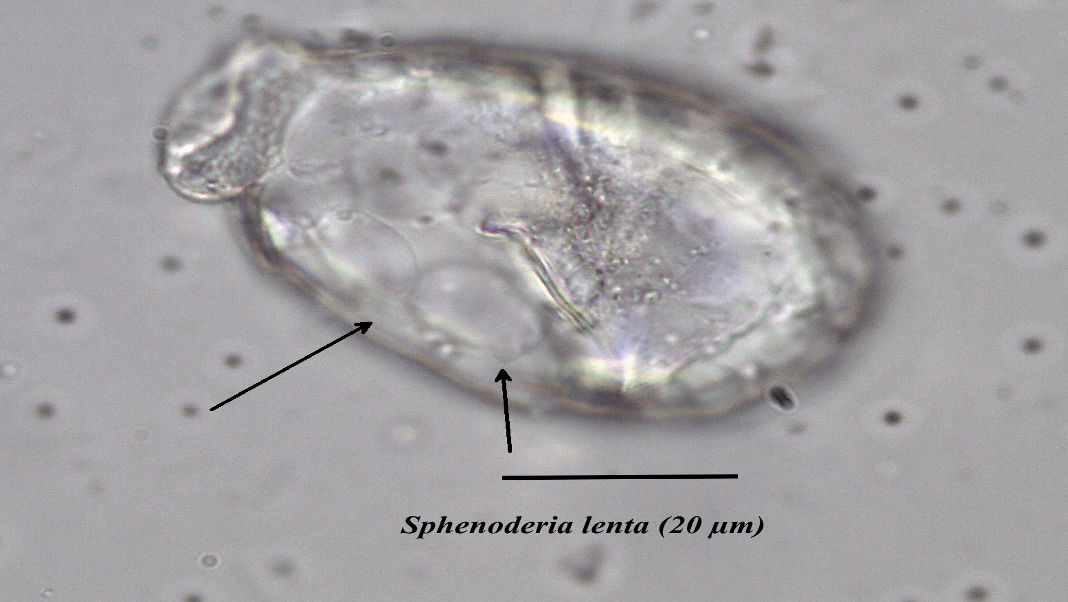

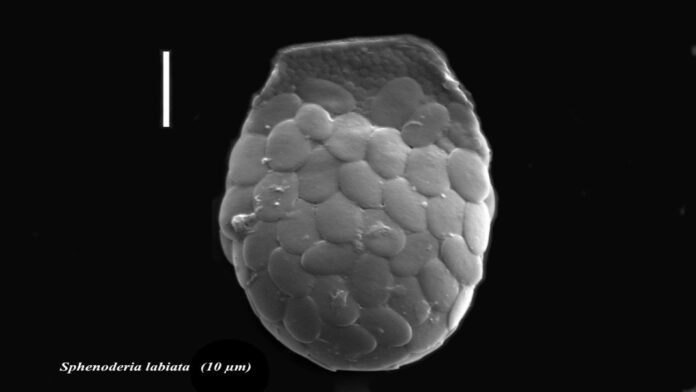

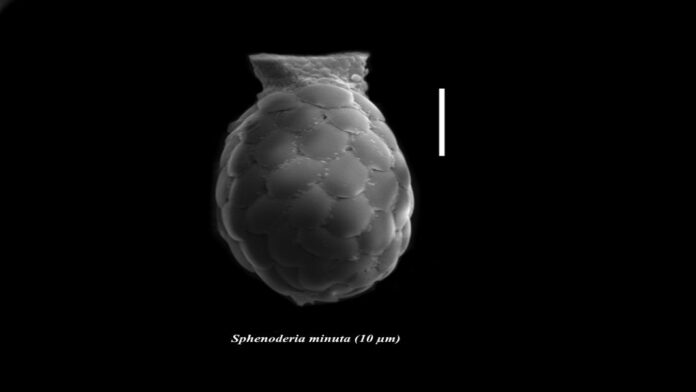

The study, published in the international journal Zootaxa, reports Sphenoderia minuta and Sphenoderia labiata from aquatic habitats in Meghalaya, while Sphenoderia lenta was found in tree moss samples collected from a conserved forest biotope in Arunachal Pradesh. Together, the findings underline the ecological richness of Northeast India at the microscopic scale.

“These findings show the rich diversity of not only large organisms, but also unicellular organisms like protists,” said Purushothaman Jasmine, lead author of the study. “Such life forms are fundamental to ecosystem functioning, yet they remain largely invisible in conservation discussions.”

Testate amoebae are single-celled organisms enclosed in delicate siliceous shells. Despite their tiny size, they play a key role in nutrient cycling and food webs in soil and freshwater ecosystems, and are globally recognised as sensitive bioindicators of environmental change.

Jasmine warned that current conservation priorities often overlook these organisms and the habitats they depend on.

“Most research is focused on charismatic species — apex predators like elephants and tigers,” she said. “There is also an assumption that soil and freshwater systems will continue to survive, even when anthropogenic pressures have crossed their carrying capacity. This attitude underestimates the survival of microhabitats.”

The discovery is particularly significant as both Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh lie within the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot, a region known for high species richness but also increasing pressure from land-use change, pollution and climate stress.

The presence of Sphenoderia species in both freshwater and forest microhabitats suggests a complex and fragile ecological balance.

Researchers say microorganisms are often the first to respond to environmental disturbance, making them early warning indicators of ecosystem degradation.

“When we ignore microscopic life, we lose the first signals of ecological stress,” Jasmine said.

The study calls for greater scientific attention to microbial biodiversity in Northeast India, including molecular research, to better understand how such organisms respond to environmental change.

In revealing life measured in microns, the researchers have delivered a broader message: protecting the biodiversity of Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh also means safeguarding the unseen foundations of their ecosystems.