By Manoranjana Gupta

Earlier courts had hinted; this one declared !

The line between sacred wealth and state revenue is now drawn in stone — धन देवता का है, सरकार का नहीं.

For decades, India’s temples — those luminous centres of shraddha, seva, and community welfare — have been governed with the paradox of reverence and control. Their doors were open to every devotee, their funds offered for the common good, yet their coffers were treated as extensions of the state exchequer.

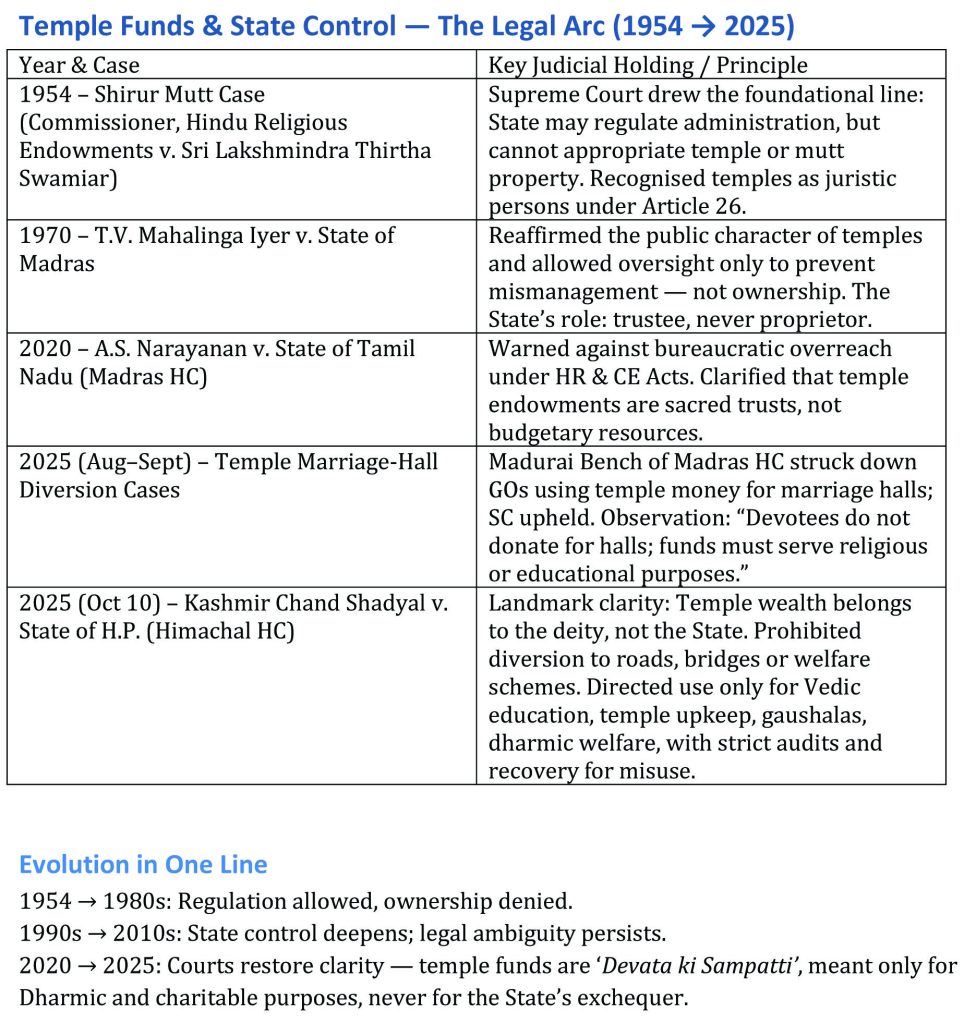

No other faith has been as liberal in sharing its spaces or as generous in offering its wealth for collective upliftment — and it is precisely this openness that successive governments have exploited. Earlier courts had spoken in scattered tones about the sanctity of temple funds. The Shirur Mutt judgment of 1954 drew the first boundaries, later rulings echoed them, but each left room for bureaucratic interpretation.

The Himachal Pradesh High Court, in contrast, has now ended that ambiguity with finality. Its October 2025 verdict in Kashmir Chand Shadyal v. State of H.P. is not a beginning — it is the culmination, the definitive declaration that the wealth of Dharma belongs to the deity alone. The line between sacred trust and state treasury has at last been drawn in stone — धन देवता का है, सरकार का नहीं.

A Judgment That Restores Dharma’s Fiscal Sanctity

When the Himachal Pradesh High Court, on 10 October 2025, delivered its order in Kashmir Chand Shadyal v. State of H.P., it did more than settle an administrative dispute. It redrew a boundary between the sacred and the secular that had been blurred since Independence.

The Bench of Justices Vivek Singh Thakur and Rakesh Kainthla held that all money offered in temples — whether in cash, kind, or gold — is property of the deity (devata ki sampatti), not of the government that manages the temple through a board or department. The court said in ringing clarity:

“Temple offerings are not state revenue. The government cannot appropriate what belongs to faith. It is the trustee, not the owner.”

This single sentence restores the moral architecture of Indian religious life. It places the State where it constitutionally belongs — as a sevak, not a swami.The Legal Lineage — How Courts Viewed Temple Property Earlier

The court’s reasoning did not arise in a vacuum. Since 1954, the Supreme Court in the celebrated Shirur Mutt case (Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments v. Sri Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar of Shirur Mutt) had held that the State may regulate the administration of temples but cannot appropriate their wealth. The Mutt, the Court said, was a juristic person — its property sacrosanct.

Later, in T. V. Mahalinga Iyer v. State of Madras (1970), the Madras High Court reaffirmed that while oversight was permissible to prevent mismanagement, the sovereign could never become the owner.

Even so, over the decades, state governments gradually expanded their control through Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (HR & CE) departments, interpreting “charitable purpose” to include secular welfare. The phrase became the loophole.

Courts occasionally protested — A. S. Narayanan v. State of Tamil Nadu (2020) condemned using temple funds for staff salaries or unrelated public works — but ambiguity remained. “Charitable” was read so broadly that roads, schools, and even relief funds were financed by temple income.

The Grey Zone of Ambiguity

This ambiguity had a price. Once temple revenues entered state accounts, they were treated as discretionary funds. In Tamil Nadu, the HR & CE Department admitted in 2021 that portions of temple income financed COVID-19 relief and general welfare. In Andhra Pradesh, part of the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanam (TTD) income was diverted to secular programmes. Kerala and Karnataka, too, used temple surpluses for road construction or employee pensions.

Thus the dharmic architecture of offerings — daan, chadhawa, bhent — was collapsed into fiscal arithmetic. Devotees’ faith was converted into an “asset class.”

Hindu jurisprudence has always distinguished between rajya ka kosh and mandir ka nidhi. The former is taxation; the latter is shraddha. Mixing them corrodes both. As the Manusmriti warns:

“A king who seizes the property of the gods or the Brahmanas becomes an outcast and shall lose his realm.” (Manu Smriti 8.394)

Yet independent India allowed this slow erosion — often in the name of “public purpose.”

Himachal’s Correction — From Trusteeship to Dharma-nidhi

The Himachal Pradesh High Court has now drawn the lakshman rekha anew. It ruled that temple income may only be used for:

– Preservation and renovation of temples

– Vedic, Upanishadic and Yoga education — Gurukuls, Pathshalas

– Gaushalas, Annadaan, Seva projects within dharmic frameworks

– Aid to orphanages, old-age homes, and hospitals directly linked to temple trusts

The judgment also directs the Temple Trust Administration to maintain audited digital accounts and publish yearly statements — ensuring transparency without surrendering ownership. In one stroke, the Court replaced bureaucratic control with moral trusteeship. It reminded administrators that they are karyakartas of Dharma, not accountants of revenue.

Why the Misuse Must End

Temple wealth in India is colossal — estimates range from ₹4 lakh crore in movable assets to another ₹10 lakh crore in land and gold. Yet Hindu temples, paradoxically, often lack funds for daily worship, priest welfare, Sanskrit education, or even basic infrastructure.

The reason is simple: appropriation disguised as management. Governments that would never touch the income of churches or mosques freely dip into temple coffers, citing state acts. In effect, the Hindu devotee is taxed twice — once by the government, again by bureaucratic overreach.

This dual taxation violates Article 26 of the Constitution, which guarantees every religious denomination the right to manage its own affairs. It also violates the spirit of Dharma-artha samāhita rajdharma — the moral duty of the State to protect, not consume, the sacred.

Swami Vivekananda once said: “The temple is not merely a house of prayer, it is the heartbeat of the nation’s moral life.” When its funds are misused, that heartbeat falters.

A Call for Replication Nationwide

The Himachal model must now become a national doctrine. Every state that controls Hindu temples under endowment acts should legislate along the same principle. They should declare temple income to be religious property, beyond appropriation.

They must also establish ‘Temple Protection Authorities’ independent of political interference.

This is not a communal assertion; it is a constitutional restitution. What the court has done is to restore parity: the same autonomy that every faith enjoys must apply to Hindu institutions too.

Where the Money Must Go — For Dharma, Not Departments

Hindu society today faces a paradox of plenty and poverty. Gold accumulates in sanctums even as Sanskrit pathshalas close for lack of ₹20 lakh a year. Sevaks who keep temples alive often live on honoraria smaller than a government peon’s salary.

The funds lying dormant in temple treasuries could endow thousands of Vedic schools, music gurukuls, classical arts centres, dharma-research chairs, and healthcare for the underprivileged — all within the spirit of ‘seva paramo dharmah’. They must finance Sanskrit schools, Ayurveda centres, dharmashalas, cultural preservation, and welfare rooted in dharmic philosophy.

That is precisely what the Himachal judgment enables: a redirection of faith’s energy to rejuvenate Sanatan Dharma itself, not the political machinery around it.

The Broader Civilisational Meaning

This verdict is not against the State; it is against statism. It rebalances India’s dharmic ecosystem by recognising that sovereignty and sanctity are different realms. One governs men; the other nourishes souls.

In Rajdharma, the king was always a guardian of Dharma, never its beneficiary. The same logic applies today. The modern Republic may regulate for accountability, but it cannot convert temples into departments.

Himachal’s judgment therefore revives a civilisational truth: “Where the temple is free, society is moral; where the temple is enslaved, faith becomes ornamental.”

Why This Matters Beyond Himachal

The case has implications far beyond the hills. It sets a jurisprudential precedent for Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Odisha, and Telangana — all of which run extensive temple boards.

If these states replicate the Himachal order, India could witness the largest restitution of religious autonomy in modern history. Thousands of temples could reclaim their funds and channel them into dharmic education, heritage conservation, and rural welfare.

Such a model would also reduce political interference and revive local participation — village committees, hereditary trustees, and community samitis who understand the temple’s soul, not just its accounts.

From Litigation to Liberation

In the past decade, devotees have increasingly approached courts seeking protection of temple assets. But litigation alone cannot replace structural reform. What India needs is a National Policy on Temple Governance grounded in three principles:

1. Deity Ownership (Devata ki Sampatti): The deity is the juristic owner; the State only supervises.

2. Restricted Use: Funds limited to religious, charitable, and dharmic welfare.

3. Transparent Audit: Digital, public records ensuring trust, not control.

If implemented, this triad could restore faith-based federalism — where every temple sustains its own ecosystem of service, learning, and community support.

Conclusion — Dharma’s Return to Its Source

The Himachal judgment is a civilisational reset. It reminds India that Dharma cannot survive on sentiment alone; it needs resources, legal clarity, and institutional autonomy.

By affirming that “temple wealth belongs to the deity”, the court has, in effect, reclaimed the moral sovereignty of Sanatan Bharat. The judgment does not pit religion against government; it demands that government remember its duty as Rakshak, not Bhokta.

May other High Courts and the Supreme Court take this cue — so that the mandir ka deepak once again illuminates not bureaucracy, but Bharat’s Atma.

Author’s Note

As one who has witnessed both the liberal heart of Sanatan Dharma and the bureaucratic indifference that often cages it, I see this judgment not merely as law but as justice long deferred. Temple funds are not relics of ritual — they are reservoirs of faith. When restored to their rightful dharmic purpose, they can illuminate Bharat’s moral and spiritual economy once again.