By Satyabrat Borah

As the bicentenary of the Treaty of Yandaboo approaches, Assam finds itself standing at a quiet but deeply significant historical threshold. Two hundred years ago, a single treaty signed far away from the soil of Assam altered the course of its destiny forever. The Treaty of Yandaboo was not just a diplomatic document that ended a war between the British East India Company and Burma. It was a turning point that pushed Assam out of nearly six centuries of political independence and into the long, complex experience of colonial rule. Looking back today, it becomes clear that this treaty reshaped not only the political map of the region but also the confidence, identity, and historical momentum of an entire people.

Before 1826, Assam had existed for centuries as a distinct political and cultural space under Ahom rule. The Ahoms, who had established their kingdom in the thirteenth century under the leadership of Chaolung Sukapha, gradually built a state that was deeply rooted in the land and its people. Their rule was not merely administrative or military in nature. It evolved as a social and cultural system that accommodated local customs, languages, and traditions. Over time, the Ahoms adopted Assamese language and culture, forging a shared identity with the indigenous population. Religious tolerance, social balance, and the inclusion of diverse communities into the state structure became defining features of Ahom governance. For nearly six hundred years, Assam resisted repeated external invasions and maintained its sovereignty with remarkable resilience.

Yet history often turns not only on external threats but also on internal weaknesses. By the late eighteenth century, the Ahom state had begun to show signs of deep internal strain. The Moamoria rebellion shook the foundations of the kingdom, weakening its administrative and military strength. Prolonged civil conflicts, court intrigues, and power struggles eroded the authority of the monarchy. Decision-making became short-sighted and fragmented. The unity that had once allowed the Ahoms to repel powerful invaders slowly gave way to distrust and division. It was in this moment of vulnerability that Assam became exposed to forces far beyond its control.

Taking advantage of Assam’s internal turmoil, Burmese forces repeatedly invaded the region in the early nineteenth century. These invasions left deep scars on the collective memory of the Assamese people. Villages were destroyed, temples desecrated, and countless lives lost to violence, displacement, and fear. The Burmese occupation was marked by extreme brutality, and even today, stories of that period evoke a sense of horror and trauma. Faced with the inability to protect their kingdom, sections of the Ahom ruling elite turned to the British East India Company for military assistance. At that moment, seeking British help may have seemed like a necessary and unavoidable choice, a desperate attempt to escape immediate annihilation. However, history would soon reveal the heavy price of that decision.

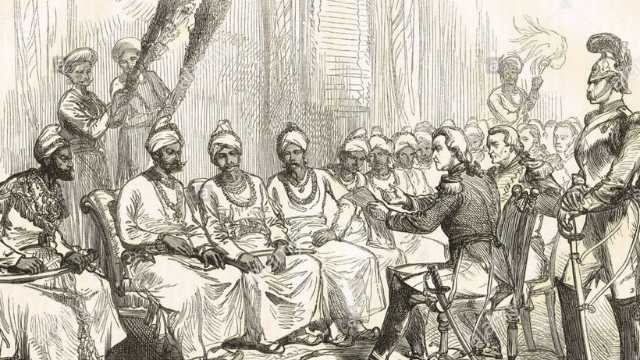

The British intervention in the Anglo-Burmese War led to the defeat of Burmese forces. But victory did not restore Assam’s independence. Instead, it paved the way for colonial control. On 24 February 1826, the Treaty of Yandaboo was signed between the British East India Company and the Burmese kingdom. Assam, which had already suffered immense devastation, was transferred to British authority without any consultation with its people. The Assamese had no voice at the negotiating table. Their land, their political future, and their sovereignty were decided by distant powers pursuing their own strategic interests.

With the signing of the treaty, Assam was abruptly transformed from an independent kingdom into a colonial possession. This shift marked the end of a long tradition of self-rule and the beginning of an uncertain new chapter. British rule brought with it profound changes to Assam’s political, economic, and social life. Some of these changes were presented as reforms or progress, but beneath them lay the logic of colonial exploitation.

To the British, Assam was primarily valuable as a resource-rich territory. Its fertile land, forests, oil reserves, and especially its potential for tea cultivation made it strategically and economically attractive. The development of tea plantations did create a new economic landscape, but the benefits were unevenly distributed. Large tracts of land were taken over for plantations, often displacing local communities. Labour was brought in from outside the region under harsh conditions, creating new social tensions. Local farmers found their landholdings shrinking, while changes in land revenue systems pushed many into debt and poverty. Assam’s economy was increasingly shaped to serve imperial interests rather than local needs.

Colonial rule also brought significant social and cultural transformations. Western education was introduced, giving rise to a new educated middle class. This exposure to modern ideas encouraged rational thought, scientific temper, and eventually political awareness. At the same time, however, colonial policies often undermined local languages and traditions. In the early years of British administration, Assamese was denied recognition as a separate language and was replaced by Bengali in official and educational settings. This decision deeply hurt Assamese society, creating a crisis of linguistic and cultural self-respect. Language, which had long been a pillar of Assamese identity, suddenly became a site of struggle.

The response to this cultural marginalisation laid the foundation for a powerful intellectual and cultural awakening. From the late nineteenth century onwards, Assamese thinkers, writers, and reformers began to assert the distinctiveness of their language and culture. Figures such as Anandaram Dhekial Phukan, Hemchandra Barua, and later Lakshminath Bezbaroa played crucial roles in reviving Assamese literature and shaping modern Assamese identity. Literary movements, language campaigns, and cultural initiatives helped restore confidence and pride among the people. In an indirect yet profound way, the colonial experience initiated by the Treaty of Yandaboo forced Assamese society to reflect on itself and articulate its identity in modern terms.

As the bicentenary of the treaty draws near, it becomes evident that the legacy of Yandaboo extends far beyond the nineteenth century. Many of the political and economic structures introduced during colonial rule continue to influence Assam today. Questions surrounding land rights, resource control, migration, and centre-state relations have roots in policies framed during the colonial period. Administrative boundaries, legal frameworks, and governance models created by the British still shape the functioning of the state in various ways.

The Treaty of Yandaboo should therefore not be remembered solely as a moment of defeat or loss. While it undeniably represents a painful rupture in Assam’s history, it also serves as a powerful lesson. It reveals how internal disunity and lack of long-term vision can weaken even the strongest of states. The fall of the Ahom kingdom was not caused only by external aggression but also by internal fragmentation. This lesson remains deeply relevant in the present, reminding society of the importance of unity, foresight, and collective responsibility.

At the same time, the treaty reminds us that a nation’s history is not built only on moments of glory. Defeat, suffering, and struggle are equally part of the historical journey. Understanding these chapters honestly allows a society to grow stronger and wiser. The colonial period that followed Yandaboo also gave rise to resistance, reform, and the eventual aspiration for freedom. The growth of national consciousness, the defence of language and culture, and the desire for self-determination can all be traced, in part, to the disruptions caused by colonial rule.

For today’s generation, the Treaty of Yandaboo should not remain confined to textbooks or academic discussions. It should be engaged with as a living history that continues to shape the present. It reminds us that freedom is never easily won, and once achieved, it must be carefully protected. Two hundred years later, the shadow of Yandaboo still lingers over Assam, but within that shadow lies the opportunity to draw strength, clarity, and purpose from the past.

If the lessons of history are understood with honesty and humility, the pain associated with Yandaboo can be transformed into a source of collective wisdom. By respecting the past, acknowledging historical truths, and remaining committed to justice, unity, and dignity, Assam can ensure that the memory of the treaty serves not as a symbol of helplessness but as a reminder of resilience. In this deeper understanding lies the true meaning of marking two hundred years since the Treaty of Yandaboo.