By Satyabrat Borah

The recent comments from Pakistani political analyst Najam Sethi have stirred fresh debate across South Asia, particularly in the context of the already strained ties between India and Bangladesh. Sethi, widely regarded as a close associate of former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, appeared on a Pakistani news channel and issued a stark warning. He suggested that India might not tolerate what he described as provocative statements coming from Dhaka and could respond in a manner reminiscent of its military actions against Pakistan in the past. Specifically, he referenced something called Operation Sindoor, implying that New Delhi could pursue a similar approach toward Bangladesh if tensions continue to escalate.

To understand the gravity of Sethi’s remarks, it helps to look at the backdrop. Relations between India and Bangladesh have deteriorated significantly since the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s government in August 2024. Hasina, who had maintained a close partnership with India for over a decade, fled to New Delhi amid massive protests and now resides there under India’s protection. The interim government led by Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel laureate and founder of Grameen Bank, has taken a different tone in its dealings with India. While both sides insist they want constructive ties, a series of incidents and statements have created deep mistrust.

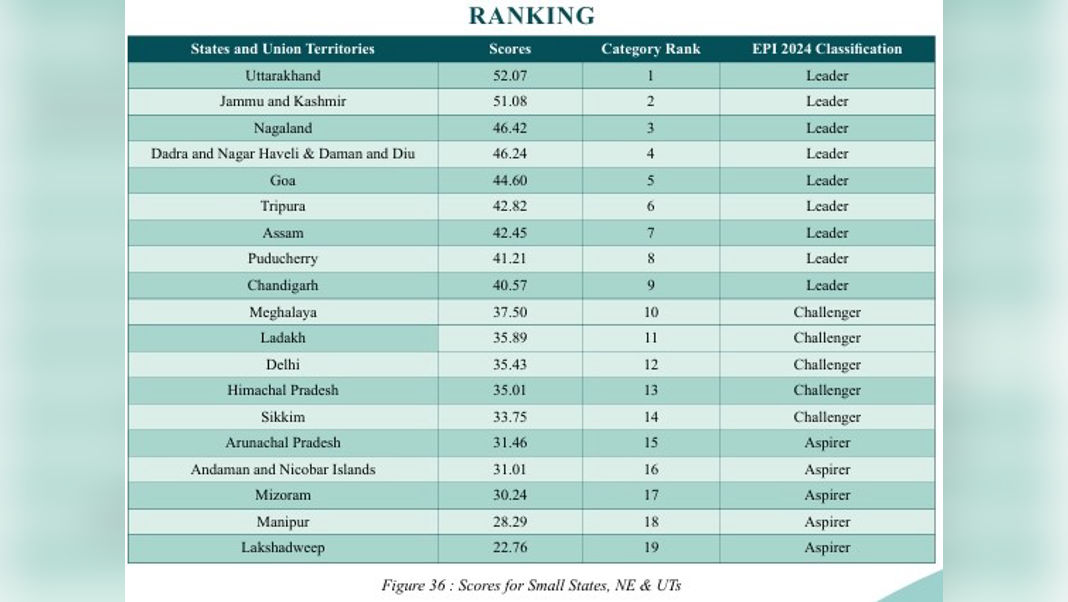

One of the most contentious moments came during Yunus’s visit to China in late March 2025. In meetings with Chinese officials and investors, he described India’s northeastern states—the so-called Seven Sisters of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura—as landlocked. He emphasized that these regions have no direct access to the sea and positioned Bangladesh as the sole guardian or gateway to the ocean for that entire area. He suggested this created immense opportunities for economic integration, particularly with China, which could benefit from using Bangladesh’s ports and infrastructure to reach deeper into South Asia.

Those words landed like a bombshell in India. The Northeast is a sensitive region for New Delhi, not just because of its geography but due to long-standing concerns about separatism, insurgency, and external influences. Leaders in Assam and other states reacted sharply. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma called the remarks objectionable and deserving of strong condemnation. BJP MP Nishikant Dubey labeled them shameful and inflammatory. The comments were seen as an attempt to undermine India’s sovereignty over its own territory by framing the Northeast as somehow dependent on Bangladesh for maritime access, even though India has invested heavily in connectivity projects like roads, railways, and waterways to integrate the region more firmly with the mainland.

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar responded with measured but pointed criticism. He highlighted that cooperation must be based on mutual respect and a shared vision rather than selective opportunism. He pointed out that India’s Northeast is rapidly emerging as a hub for regional connectivity through initiatives under BIMSTEC and other frameworks, with expanding networks of infrastructure that reduce any perceived isolation. India has repeatedly stressed that it does not allow its territory to be used for anti-Bangladesh activities, directly refuting Dhaka’s occasional accusations that exiled Awami League members or others are plotting from Indian soil.

Against this simmering friction, Sethi’s intervention adds an unusual layer. As a seasoned commentator known for his candid takes on Pakistani politics and regional affairs, he is not someone whose words are easily dismissed. His proximity to Nawaz Sharif lends him credibility in certain circles, though it also colors his perspective with Pakistan’s own historical rivalry with India. In his interview, Sethi argued that Bangladesh was essentially threatening India by talking about what it might do to the Seven Sisters. He predicted that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, with his reputation for a firm and assertive foreign policy, would not simply overlook such rhetoric. Drawing a parallel to India’s past conduct toward Pakistan, Sethi invoked Operation Sindoor as the kind of decisive step New Delhi might contemplate.

Operation Sindoor refers to a military campaign India launched in May 2025 against Pakistan. It came in response to a horrific terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir, on April 22, 2025, where militants targeted civilians based on religion, killing 26 people. India identified the attackers as linked to Pakistan-based groups like Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Taiba. On May 7, India executed precision missile and drone strikes on terror infrastructure in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir, marking one of the most significant cross-border operations since 1971. The operation avoided direct ground invasion or targeting of Pakistani military or civilian sites initially, but it escalated into a brief five-day conflict involving air engagements and further exchanges. It demonstrated India’s advances in standoff weaponry, intelligence, and rapid response capabilities, establishing what many analysts called a new doctrine of calibrated but forceful retaliation against terrorism without escalating to full-scale war.

Sethi, reflecting on that episode from Pakistan’s viewpoint, suggested that India views itself as an emerging great power that must project strength. In his words, there is a prevailing sentiment in New Delhi that the country cannot afford to appear weak when faced with perceived threats or provocations. By linking Bangladesh’s statements to this mindset, he implied that rhetorical challenges to India’s control over its Northeast could trigger a robust response, perhaps not identical to Sindoor but comparable in resolve and impact.

Of course, such predictions are speculative and come from a Pakistani lens, where anti-India narratives often find receptive audiences. There is no public indication that India is planning any military action against Bangladesh. New Delhi has consistently emphasized its preference for peaceful, friendly relations with Dhaka. In December 2025, the Ministry of External Affairs reiterated that India has never permitted its territory to be used against Bangladesh’s interests and called for dialogue based on mutual benefit. Diplomatic channels remain open, and both countries continue to engage on issues like trade, border management, and water sharing, even if the warmth of the Hasina era is absent.

Yet the underlying tensions are real. Bangladesh’s interim leadership has sought to diversify its foreign relations, deepening ties with China and even Pakistan in some symbolic ways. Yunus’s China visit and his framing of the Northeast as an economic opportunity for Beijing raised eyebrows in India, which sees the region as strategically vital and has countered Chinese influence through projects like the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway and enhanced Act East Policy initiatives. Meanwhile, accusations fly back and forth: Bangladesh has claimed that anti-government elements are operating from India, while India denies this and points to the need for Dhaka to rein in anti-India rhetoric and activities.

Sethi’s comments, amplified by outlets like Firstpost, have reignited discussions about how far the rhetoric might go and whether miscalculations could lead to unintended consequences. In a region scarred by historical conflicts, including the 1971 war that created Bangladesh out of Pakistan with India’s decisive help, any talk of military parallels carries heavy weight. For ordinary people in both countries, the stakes are high—economic interdependence, shared rivers, millions crossing borders for work and family, and a history of cultural ties that transcend politics.

This episode reflects the challenges of neighborhood diplomacy in South Asia. Trust, once eroded, is hard to rebuild. Statements intended for domestic or international audiences can spiral into broader confrontations. Najam Sethi’s warning, while perhaps exaggerated for effect, underscores a fear shared by many observers: that provocative words, if not tempered by restraint, could push even close neighbors toward dangerous escalation. Whether India would ever contemplate anything akin to Operation Sindoor against Bangladesh remains highly unlikely given the deep people-to-people links and mutual vulnerabilities. But the mere mention serves as a reminder of how fragile regional stability can be when historical grievances, geopolitical maneuvering, and domestic pressures collide.

As the situation evolves, much will depend on quiet diplomacy, backchannel talks and leaders on both sides choosing de-escalation over confrontation. India has made clear its desire for friendship, but it has also shown it will defend its core interests firmly. Bangladesh, navigating its post-Hasina transition, faces the task of balancing internal reforms with careful external relations. In this delicate balance lies the hope that cooler heads prevail and the subcontinent avoids yet another cycle of tension.