By Bhaskar Saikia

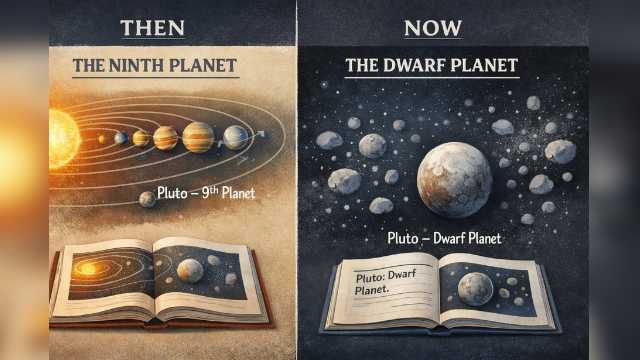

Every year on 18 February, astronomers and space enthusiasts observe Pluto Day, marking the discovery of Pluto in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh. For decades, Pluto held a special place in textbooks and in the public imagination as the 9th planet of our Solar System. Yet in 2006, Pluto was reclassified as a dwarf planet, losing its long-held planetary status. At first glance, this may seem like a scientific blunder or an embarrassing correction. In reality, it represents one of the greatest strengths of science: its willingness to change in the light of new evidence.

The story of Pluto began even earlier, in 1916, when Percival Lowell predicted the existence of a “Planet IX” beyond Neptune. Although his calculations were not fully accurate, they motivated a systematic search that eventually led to Pluto’s discovery. Given the knowledge and observational tools available at the time, classifying Pluto as a planet was a reasonable conclusion. Science always works with the best evidence available at a given moment.

As the 20th century progressed, technological advances transformed astronomy. More powerful telescopes revealed that Pluto was not unique. Astronomers began discovering many similar icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt, a vast region beyond Neptune. Some of these objects, such as Eris (discovered in 2005), were comparable to Pluto in size. This raised a fundamental question: if Pluto is a planet, should all these similar objects also be considered planets? Without a clear definition, the number of planets in our Solar System could grow rapidly and arbitrarily.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union introduced a formal definition of a planet. One of the criteria was that a planet must have cleared its orbital neighbourhood of other debris. Pluto did not meet this condition and so it was placed in a new category: dwarf planets. Importantly, Pluto itself did not change: its orbit, size and composition remained the same. What changed was our understanding and our definition, refined to accommodate new discoveries.

This is not a sign of weakness in science but a sign of intellectual honesty. In many systems of belief, changing one’s position is seen as inconsistency. In science, it is a virtue. A scientific idea remains valid only as long as it best explains the available evidence. When new data appear, science updates its conclusions. This self-correcting nature of science is what has enabled humanity to move beyond many deeply rooted misconceptions, such as the time when people believed that the Sun revolved around the Earth, that diseases were caused by bad air or evil spirits, and that continents were fixed and immovable.

This spirit of correction does not remain confined to space science; it extends across every scientific discipline, particularly in fields such as taxonomy — the science of naming and classifying organisms. Taxonomy is far more than a system of just providing scientific names. It represents our evolving understanding of how organisms are related to one another through evolution.

As new evidence becomes available, especially from molecular and DNA analysis, scientific names and classifications often change. A species once placed in a particular genus may be reassigned, families may be reorganised and historically accepted names may be revised. What was once thought to be a single species can later be recognised as several distinct ones, while a genus believed to be natural may turn out to be an artificial grouping. These shifts do not indicate instability, but progress in understanding.

To those outside the field, such changes can appear confusing or unnecessary. In reality, they show science actively refining its tree of life, correcting earlier assumptions and moving closer to an accurate picture of biological diversity.

In academic life, this distinction becomes important. A good teacher knows what was accepted as true in the past, but a great teacher remains aware of what has changed. Failing to keep pace means holding on to outdated classifications, obsolete ideas and inherited errors — the academic equivalent of continuing to call Pluto a planet simply because that is how it was once learned.

Pluto Day, therefore, is more than a celebration of a distant world. It is a reminder that science is not built on rigid dogma but on continuous questioning, testing and correction. Its authority does not come from being unchanging, but from being open to revision. That humility is precisely what has driven scientific progress, shaping a world transformed by medicine, technology and our expanding understanding of the universe.

Pluto was not ‘demoted’ in any tragic sense. Instead, its story highlights the dynamic nature of scientific knowledge. Science grows, adapts and corrects itself, and that is why it remains our most reliable way of understanding the natural world.

(Bhaskar Saikia is a taxonomist, currently working in Zoological Survey of India, Shillong. He can be reached at mail.bhaskarsaikia@gmail.com)